Take Back Your Freedom: 5 Steps to Abolishing Mom or Dad Guilt

I’ve never met a mother who doesn’t battle with mom guilt. It seems less common for fathers; however, I also know many fathers who are influenced by guilt. Lately, my husband, Peter, and I have been forced to come to grips with exactly how many of our daily parenting choices are governed by mom/dad guilt.

We each brought one living child into our marriage from divorced situations. Peter is in the process of adopting my middle daughter; I am stepmother to his son. As a result, Peter and I are variously parents to a stepchild, a child in heaven, an adopted child with a medical condition, and a baby girl newly born into our marriage.

Over the past months, it’s become abundantly clear that our behavior towards our children from former marriages is ruled by guilt. We both parent each other’s child in a more healthy and balanced way than we parent our own–precisely because guilt is not present in that relationship.

Blending families has the unique capacity to be the greatest adventure of your life or an absolute living nightmare. But every family—even those blessedly intact—struggles with the guilt that seems to plague parenting like a shadow. Every parent occasionally makes less-than-balanced decisions, based on shame, fear, anger, pity, or even sheer exhaustion.

what is mom/dad guilt?

Guilt arises when we fall short of a self-imposed or culturally-mandated standard or ideal of behavior. Motherhood and fatherhood are the most primordial human identities; they are embedded in our universal subconscious. The archetype or prototype of motherhood against which I am constantly measuring myself seems to communicate that I can never be enough or do enough for my children.

Sometimes, to cope with this self-sabotaging psychological loop, I think about the Hebrew word for sin, which is חטאה (hhatah) and literally translates to “miss the mark.” If I think about sin or transgression as falling short of meeting an ideal, it helps me avoid the self-condemnation spiral and instead decide to incorporate the experience into doing better next time.

Guilt is a heavy word; the term “mom guilt” has become an almost lighthearted colloquialism to cope with the serious implications of what it means to feel inadequate as a mother. But I think it is a mistake to make light of the issue or to mock women or men when they feel guilt associated with parenting. It almost always targets a serious emotional wound or psychological insecurity in the parent that deserves to be spoken, heard, and processed.

The first step to processing is almost always to give the emotion a name; identify the enemy in order to conquer it. The problem is that parental guilt is so ubiquitous that it’s almost a daily experience for many parents. It tends to underlie so many of the ways in which we think about ourselves, our children in reference to ourselves, ourselves in reference to other parents, or ourselves in reference to that primordial, archetypal parent that lives in our subconscious mind.

A second problem is that guilt is such a powerful emotion that it can become crippling in a heartbeat, especially if there are ingrained neurological pathways of self-loathing and despair already present in the parent’s mind.

my struggle with mom guilt

I have fought self-loathing and despair for most of my adult life. I’ve also struggled with guilt about what I can and should be since my teenage years. But never have I encountered so powerful and overwhelming a guilt as mom guilt.

My second daughter, Cecilia, was born a month to the day after the sudden and unexpected death of my first daughter. At 9 months of age, Cecilia was diagnosed with a one-in-a-million worldwide autosomal recessive genetic disorder.

Doctors and therapists tell me that these things are not my fault, and yet, I feel I could not provide my second daughter with the two things that should be every child’s right by just and natural law: a healthy, fully functioning body and a stable, secure environment in which to grow up.

Cecilia is now weeks away from turning 4, and in the past 2 years has gained an adopted father and brother, a service dog, and a new baby sister. She is happier and healthier than I have ever known her to be. And yet, my guilt when it comes to Cecilia influences even the most minute interaction I have with her every single day.

I feel I can never do enough or be enough to make up for the broken history into which she was born. For the first years of her life, I fixated obsessively on how to optimize her health and development, taking her to an endless string of specialists and therapists. But instead of resolving her issues, the medical and therapeutic world caused her to develop some massive trauma, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive patterns that now make her incredibly difficult to parent–an unforeseen outcome that adds new and complex layers to my already flourishing patterns of mom guilt.

my father’s wisdom

If I were to tell you the life story of my father, it would encompass massive trial and tribulation, loss, grief, risk, fear, rejection, and despair. And yet, anyone who meets my father regards him as a man profoundly worthy of respect and deference, a man who owns his own wildly successful and lucrative business, and a man surrounded and desired by his children and grandchildren. I am one of my father’s 5 children, and we are all extremely different people with a diverse spectrum of needs. It constantly astounds me that my father has won the trust and hearts of each of his (now adult) children.

And yet, as I go to him again and again with my own parenting struggles, I begin to understand how he has faced and overcome similar or identical issues in his own journey as a parent. If there is a steely and seasoned veteran against dad guilt, it is my father.

I have said before that I believe parenting is the hardest thing that most of us will ever do. One of the most difficult parenting lessons that I am still in the process of learning is deceptively simple, and yet it’s the one I feel is most intimately connected with parenting guilt:

1. it’s not about you

In the rare moments when my anxiety and frustration has pushed my father to respond with this statement, I am reduced to silence and deep contemplation. Humility is difficult for everyone, but most difficult, I think, for those who struggle with pride.

I like to think that most problems or issues I encounter are about me because then I know I can control, manipulate, and influence them. When it’s not about me, the unknown elements contribute to an utter lack of control, which, for me, is personally terrifying.

It’s easier to believe that my problems can be solved by troubleshooting something in myself. It’s more overwhelming to approach parenting when I realize that simply working harder will not solve the problem.

Believing that it’s not about me is, I think, the key to unravelling the guilt spiral. It’s also why Peter is a better parent to Cecilia and I am a better parent to his son. When it comes to the children that are not biologically ours from broken histories, we are able to both see and prioritize what is objectively best for that child, without guilt acting as both master and commander.

Peter is the only father Cecilia has ever known and the best father I could have asked for her to have. He is determined to view her without her physical and mental limitations defining her. In discipline, education, and bonding, he allows his action to be defined by what’s best for her emotionally and developmentally, and not by what makes him feel better about himself. He says I do the same with his biological son–my stepson.

But it’s not enough to say we’re better parents to each other’s biological children from broken pasts. Instead, we need to face up to our own inadequacies and find a way to challenge and overcome them without our children paying the price or abandoning ourselves to despair and self-loathing.

Reciting it’s not about me like a mantra has been helping to disengage myself from the neurological whirlpool of guilt when I feel I’ve done something to cause one of Cecilia’s meltdowns. The truth is that I can make educated guesses about what Cecilia is thinking or feeling, but she herself doesn’t really understand what she is feeling and has limited ability to communicate it with any accuracy. She’s stuck in her own loops of emotion and processing, stuck in her own perceptions of the world and the people surrounding her, and stuck in her own experience of this thing we call human life.

And yet when tears are coursing down her little cheeks or she’s screaming until her skin turns visibly blue, I begin to drown in guilt and fear that I have single-handedly caused all of her issues in my feeble and foolhardy attempts to help her. These are the moments when it becomes most critical to ground myself in reality–in a version of events where I am neither well-intentioned villain nor helpless victim.

To abolish myself as a victim, I needed to transform the way I understood my story. I needed to hear and believe:

2. you’ve done the best you could with the resources you had

I can’t count the amount of times my father has repeated this to me over the past few years–through my divorce, through my first daughter’s death, through Cecilia’s diagnosis. And yet, some part of me always rejected it, illogically countering that I should have found a way to do better regardless.

There’s a type of hidden pride in rejecting this lesson, as though I both expect and require of myself a superhuman level of control and prognostication. I have trouble accepting that life, death, and the choices of other people are beyond my control, and I can’t foresee what the future will bring. I have trouble accepting my own limits as a human being and therefore my own limits as a parent.

But I think my dad is so good at this lesson because he has had to learn humility in the face of mistakes, risks, and failures and reassess his self-perception again and again. It’s one of the most unromantic and unsensational things you can say about yourself, and yet it’s also one of the most true. If you are a disciplined person with high standards for yourself and other people, then you are probably always doing the best you can with the resources you currently have at hand.

Every adult has more resources than a child simply because aging allows us to acquire resources. So it makes sense that a younger version of yourself would have fewer resources than the current or future version of yourself. It is both unfair and unrealistic to expect yourself to behave or act according to experiences or resources that you do not yet have. It is more unfair and unrealistic to require such action from your child. This is why it’s so important to remember that parenting, at the end of the day, is not about you.

In saying that you did everything you could with what you had available to you at the time, you are able to rewrite a version of events in which you have damned yourself to being both the villain and victim of your own story. Instead, your story can evolve into a continuous coming-of-age tale where you grow through your failures into the hero that you are constantly in the process of becoming.

Because that’s the one thing that unites all hero stories:

3. never stop trying

A hero is never more heroic than when he or she climbs from the nadir of despair to the zenith of success. A pregnant woman is never closer to childbirth than when she enters transition–a stage of labor where she despairs that she can no longer endure the pain and has failed at bringing forth her child. Transition makes midwives and doulas smile softly and speak words of hope and encouragement because they know that a baby is usually only minutes away from taking that first breath.

There is something profoundly human about being forced to intimately encounter the worst parts of ourselves–the parts we wish didn’t exist–and choosing to battle through our failures or shortcomings to the other side. Because no human exists without weaknesses and inadequacies, we are all inspired by those who conquer–if only for a matter of days or weeks–their own inadequacies. It gives us hope in our own ability to do so.

There is nothing more fundamentally human than to never stop trying, and so I think there is nothing more fundamental to parenting than to never stop trying. Just as the ancient Hebrews believed that sinning was missing the mark, we can approach ourselves realistically to understand that we are never going to meet our own standards of perfect parenting–but that this reality doesn’t make fighting for that ideal and for those standards any less worth our time or energy.

This is paradoxical, complex, and difficult to implement–yes. However, it is also deeply, deeply human. Our history as a species has been this story. A vision of an ideal worth fighting for, followed by a battle for that ideal, followed by failure to accomplish that ideal, followed by troubleshooting and trying again, followed by an arrival closer to the vision–all without ever truly achieving the ideal.

Ideals are evanescent, meaning they are constantly retreating while you are constantly pursuing. This can get into long discussions of our ability to cognitively postulate the concept of infinity without ever actually comprehending it, so it is enough to say that the oldest and most essential human story is the story of the myriad failures and successes achieved along the path of striving for an ideal.

Parenting, it seems to me, is no different.

I regard my father with a level of hero-worship because of the parent he has been to me. Peter regards his mother in the same way. And yet, if you spoke directly to either my father or Peter’s mother, you would be met with little other than humility and an affirmation that hard work, the desire to help their children, and their drive to never stop trying has defined them as parents.

The sheer love and admiration that these people trigger in me and Peter drive us to keep trying when we fail. Our own parents provide a standard against which we frequently measure ourselves, and that is okay. We are half the age of our parents, with far fewer physical and emotional resources, but we strive to become like them day by day because they both participate, like Plato’s Forms, in the Supreme Mother and Supreme Father that live in our subconscious memories.

This Supreme Mother or Supreme Father can act as a North Star to guide you when you are lost in the fog of endless becoming. As long as you never stop trying to become more the kind of mother or father that you are measuring yourself against, then you can never accurately state that you have failed. Believe that you are doing the best you have with the resources available to you at this moment, and remember that it’s not about you.

And if you can’t . . .

4. be gentle with yourself

Since I was a teenager, my father has been quoting Max Ehrmann’s 1927 Desiderata poem to me: “Beyond a wholesome discipline, be gentle with yourself.” I am frankly terrible at this. But the older I become, the more I appreciate the depth of its wisdom.

For most of Cecilia’s life, I have been running myself ragged in an attempt to become a better person for her and to serve her better. I put her above myself constantly–which I believe to be an essential role of a parent–and yet, with time, it became apparent that I was doing it at extreme personal cost.

We do not become less human when we become parents; we become more human. We live closer to and are more intimately connected with those visceral realities of the finite limitations of being mortal. We know what it’s like to delay emptying our bladders or to become utilitarian about feeding ourselves. We know what it’s like to go with too little sleep too many nights in a row and to be chronically just so, so tired. We know what it’s like to put our children before ourselves. . . all of the time.

It’s impossible to not feel drained or spent to the point where the glass is no longer half full or half empty; it’s just empty. And when it’s empty physically, it’s impossible not to doubt that it will ever find a water source again.

Physical and mental weakness go hand in hand. Sleeplessness and depression go hand-in-hand. There are few things that a bite to eat and a night of good sleep cannot go a long way towards improving. Self-care is often the last thing that we want to do as a parent. . . but it is simultaneously the one thing that we can do that has the capacity to fuel everything else.

The better care you take of yourself, the better care you can take of your children. Your children benefit from not being hyper-fixated on. They benefit from not being the center of attention. They benefit from independent play.

Take these moments to take care of yourself because the one guarantee is that your children will benefit more from the genuine and unstressed moments of engagement with you when you are well-slept, clean, healthy, and satiated, than those frantic, stressful moments of trying to check one more thing off your list when you are sleep-deprived, hungry, in pain, and in need of a shower.

Parenting is not about you. It requires you to step outside of yourself to be fully present with your child. This is nearly impossible if you haven’t eaten in hours, you need to pee, your back hurts, or you only had six hours of sleep last night. Parenting without self-care requires a superhuman level of selflessness for it not to inevitably explode in resentment or despair. At every moment, you’re doing the best you can with what you have, and if you’re under-slept or under-fed, what you currently have is a lot less than what you could have. Take care of yourself, then come back and try again. And if you try again and fail, remember that your whole life is a story of trying again and failing, and it is that resilience and endurance that makes you most beautifully human.

So be gentle with yourself. It makes you a better parent. But even a fully rested and healthy parent can sabotage engagement with a child if that parent tries to force an agenda from that engagement.

This is why it is both most difficult and most necessary to:

5. meet people where they are

From about 7 months of age, Cecilia was regularly seen by visual, physical, and feeding therapists. These weekly sessions were intended to provide me with the resources to help Cecilia with her multiple developmental delays, but I treated them less like resources and more like a curriculum, complete with homework that I needed to accomplish.

I was informed by Cecilia’s visual therapist that she would need to demonstrate a list of some 150 skills in order to enter a free preschool through the county that was designed specifically for children with visual impairment. Included on this list were things like taking objects in and out of a container and coloring with crayons. The therapist and I set about trying to make Cecilia learn these skills so she could enter the preschool on time.

In one particular session, Cecilia had a full-blown meltdown because her visual therapist tried to force her to put objects back into a container that she had taken out. Because Cecilia has been physically restrained by doctors and nurses during medical procedures for most of her life, she cannot handle anyone controlling or forcing her body into some specific action. I spoke at length with the visual therapist about this issue and was met with apologies and justifications that if I wanted Cecilia to enter this preschool, we needed to develop these skills prior to that deadline.

When I married Peter, we moved out of the county that offered the preschool for visually impaired children. In the past couple of years, Cecilia has thrived from the lack of pressure, force, and focus that I used to impose upon her. I have simply been too busy being pregnant, moving, and blending families to try to force Cecilia to meet arbitrary deadlines.

I used to spend 10-15 minutes daily trying to force Cecilia to color with crayons. In recent months, I began coloring with her new big brother, and Cecilia organically wanted to join in. Now, she’s regularly scratching her own doodle sheets with crayons and decorating our wooden deck with sidewalk chalk.

As parents, we are sometimes told that our children should be somewhere developmentally that they just are not. Cecilia has had global developmental delays since infancy, and I have struggled immensely to accept her for what she is. No one likes to be forced to do something on someone else’s timelines, and for children with medical conditions, this is particularly and tragically acute. Children are truly little human beings with emotions that include obstinacy and desire for autonomy. They want to prove to themselves and to the world that they can do it by themselves. We, as adults, are not that different.

As parents, we struggle with imposing our goals, preferences, and deadlines on our children. But just as beyond a wholesome discipline, we need to be gentle with ourselves; beyond health and safety concerns, we need to give our children as much freedom and autonomy as possible. We need to ignore the voices in our heads telling us our children must meet specific milestones on time and instead, meet the child where the child is.

Force and pressure can combine to implode marriages and familial relationships alike. When we force or pressure our children to measure up to expectations that they are simply not ready for, we are setting both them and ourselves up for failure. We then feel guilty for pressuring them and guilty that we failed to make them meet the desired goal.

But both those guilts pale in comparison to the guilt that we impose on our children when the whole failed attempt causes them to feel that they have disappointed us.

Pressure very literally produces nothing positive for the mental health of parent or child. A better option is to provide endless opportunity for the child to test or challenge his own limitations, with his own agency orchestrating the process. But it is difficult–sometimes very difficult–to take a back seat.

My father has always met me where I am. He never needs to pressure me because his endless generosity of spirit and intense work ethic together inspire me to be everything that he wants from me and more.

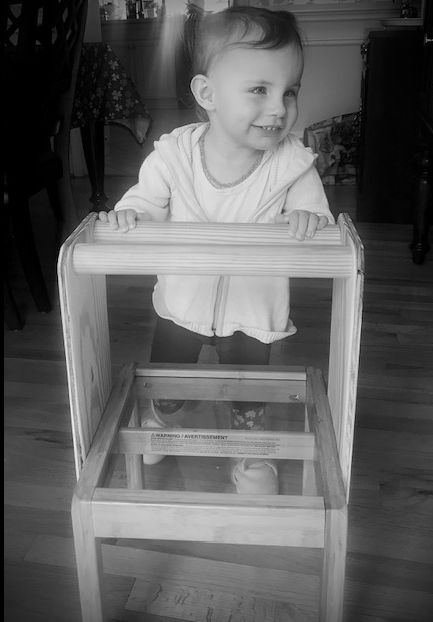

I am about to turn 37 years old, and I cannot stop wanting my parents to be proud of me. Our 7-year-old son cannot stop asking us to watch his attempts to learn and improve because he so desperately craves our approval. Cecilia cannot disengage from her obsessive psychological loops without verbal approval from us. And our newborn daughter radiates with joy when we tell her how strong and beautiful she is for practicing her standing–and also that it’s okay for her to be what she is: almost five months old and unable to support her own weight.

stepping through the guilt

Abolishing mom/dad guilt doesn’t happen overnight. You need to take it one day at a time, one step at a time. Just try to remember; it’s not about you. Your child is not your science experiment, your homework, or a component of your portfolio. In providing your child with the opportunity to accomplish the desired goal, you’ve done your best with the resources that you have at this moment. Your child is doing the same. Don’t require that his or her best equal yours. It cannot and will not.

Never stop trying. Continue to offer opportunities for growth and development. The more opportunities a child is given to practice a skill, the more confident and engaged in developing that skill he or she will become. Encourage attempt after attempt without shame. Be gentle with yourself and your child. No one becomes proficient after only a few tries. Instead, foster a wholesome discipline in both of you. Make time for rest, processing, and emotional engagement that requires nothing more from both of you than affection and desire to be with one another.

Meet your child where he or she is. Remember that this is no more or less than you ask from your own parents: to accept and love you for what you are at this moment, instead of shaming, guilting, or manipulating you to become more of what they want from you. This will foster a profound love, respect, and trust that can last beyond a lifetime.

abolishing the guilt

Abolish: to end the observance or effect of (something, such as a law) : to completely do away with (something).

– Merriam Webster

Is mom/dad guilt so ancient that it can be considered part of natural law? Is it a biological mechanism with the intended function of promoting and optimizing the survival of the offspring? Is it a mere cultural phenomenon or inbred byproduct of a patriarchal society?

When your child is screaming and you are spiraling, it doesn’t really matter if it’s all of the above or none of the above. What matters is that you’re feeling it, and it’s universal enough that most (if not all) other parents recognize it. What matters is that it rarely serves to make you into a better parent.

In the Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne, the intention behind forcing Hester Prynne to publicly wear a bright red A that labels her an adulteress is to create so powerful a social and psychological prison in her mind and heart that it eliminates the need to physically imprison her. I think mom/dad guilt does the same thing. The psychological and social punishment that we self-inflict when we feel we are failing our children accomplishes little other than trapping us in our own feelings of inadequacy and stagnation.

In other words, neither shame nor guilt have the real capacity to effect change. My father never needs to guilt or shame me into wanting to do better to make him proud; the father that he is simply makes me want to do better and make him proud. My own impulse to shame or guilt myself into being a better mother to Cecilia does not make me into a better mother; accepting that both Cecilia and I are constantly engaged in a process of trying, failing, succeeding, and becoming makes me into a better mother.

I write this post more for myself than anyone else. I tell my story because it helps me understand my story. I struggle with guilt, shame, self-loathing, and depression, and I’m looking for a path forward. Hating and punishing myself moves me backward.

With time, and with slow, excruciating self-control, I’m learning to breathe instead of plunge into guilt and despair. I’m learning that the key to my self-imposed manacles is already in the lock. And I’m learning that my children are better served by me when I troubleshoot and try again than when I wallow in guilt and failure.

The better care I can take of myself mentally, physically, and psychologically, the more directly my children benefit. There is no secret to great parenting; there is only discipline, consistency, the expectation that you will not meet the ideal, and the decision to do better tomorrow.

To be a good parent, you need to accept your humanity. You need to accept your child’s humanity. Take accountability for your transgressions, yes. But also take ownership of your capacity to heal the wounds you inflict and to improve upon your weaknesses. Silence the guilt and take back your ability to forgive yourself. Reclaim your desire to stand up and try harder.

These are the moments your children will most remember. These are the moments that have the ability to set you both free.

Well written as always my friend. What I wonder is if we in the US deal with more parental guilt partly based on the methods we choose to parent with. Currently one of the books I am reading is Hunt, Gather, Parent and the author address in the book how Europeans and Americans parent differently than many other parts of the world. I wonder how much of the guilt we feel stems from these differences, and the tendencies we have to lead more child-centric lives vs parent/family centric.