The Voice of Depression

We’ve all heard it. That thin, creeping tone growing louder until you can hear nothing else. That small, insidious whisper that tells you exactly how worthless you are. Sometimes it begins as anger, bombastic and self-righteous, flaunting its sense of injustice, slinging blame at everyone and everything else. After the anger is spent, the voice creeps in–quiet at first, softly suggestive. Somehow, it never grows in volume. It doesn’t need the inflation of rage. It’s perfectly content infesting every brain cell, one by one, until its twisted truth is all you can hear.

Most parents have experienced depression while parenting, postpartum or otherwise. My theory is that this is because parenting forces you face to face with the worst parts of yourself: the parts you want to hide, that you wish didn’t exist, that you’ve never really figured out how to cope with. It forces an encounter with that terrible, starving child inside of you that no amount of years can ever erase. The miserable orphan inside of each adult is incapable of sitting by silently watching. He will inevitably escape, scream, fight, and flee, leaving behind neurological chaos.

No parent enters parenthood having figured out this whole thing called human existence. None of us have plumbed the depths of life, death, love, and hate until no mystery remains. The path to adulthood consists in developing survival mechanisms to cope with the complexities inherent in memory, desire, truth, and becoming. And when we choose to become parents or we become parents without intention, the reality of exactly how unequipped we are to deal with life can come crashing down with the force of a tsunami.

But the truth is that parenting isn’t that different than growing up. You’re still taking it a day at a time and getting through each crisis, minor or major. You’re still developing small habits of experience that increase endurance or decrease recovery time. You don’t have all the answers, and you are still at the mercy of your weakest character traits.

And yet, it is also true that you arrived on top of this mountain called parenting by choice or chance, and your perspective on life has increased proportionately. You are no longer just a child becoming; you are now a child becoming a parent… perpetually. The self-evolution never stops; if anything, it increases with the speed of a freight train.

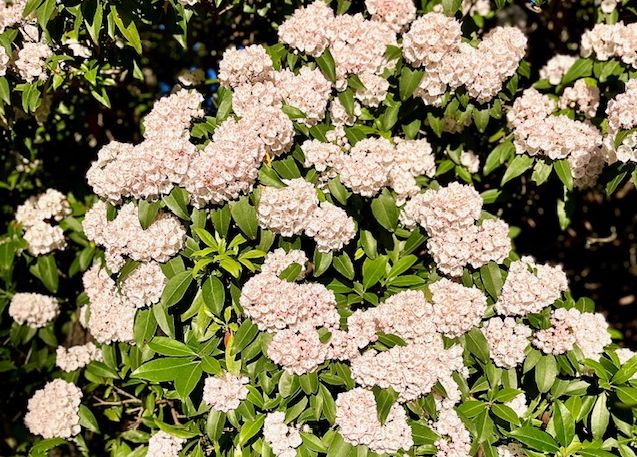

Children are dominated by reptilian and mammalian neurological processes; the neocortices of children have not developed to the point where we can call them truly human in terms of critical thought, reasoning, self-control, and empathy. The process of childhood and the job of parents are to guide the child through this maze of self-becoming, self-awareness, and, in the long-term, thinking of others before themselves. Many of us consider ourselves still children before we became parents, but parenting does not elevate us to a pinnacle or even a plateau of self-becoming. Instead, our mutability grows, like plants in the springtime, responding to a sun that rises each day with ever greater light and heat.

Because children are creatures of impulse and self-occupation, they trigger feelings of heroism, self-sacrifice, and martyrdom in their parents. It’s all too easy to wander off into branching pathways of feeling like we can never do enough, give enough, be enough—that all we do, in fact, is serve these little people who are fundamentally incapable of receiving with reciprocity–who seem to just take and take and take until we feel we have nothing left to give.

But that’s one of the greatest lies of parenting. There is always more to give. The only way there is nothing left to give is if you listen to the voice long enough that you choose to end everything.

Only then are you truly incapable of giving more.

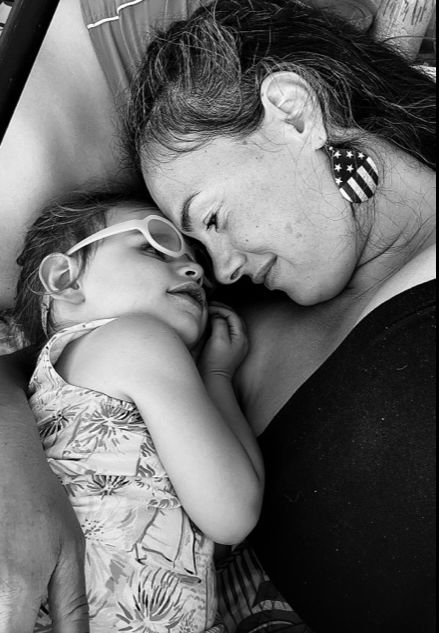

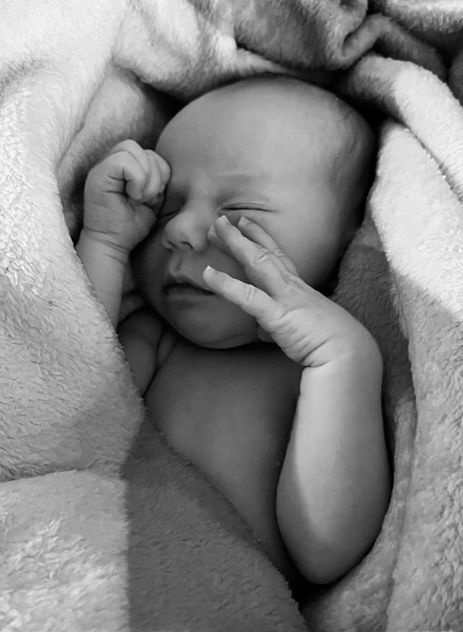

And it’s also a lie that there is no reciprocity. For those of us lucky enough to have children without severe brain injury or disability, there is profound reciprocity; it’s just the reciprocity of a child. This can be as simple as the radiant smile of a newborn or the first, spontaneous, “I love you, Mama,” from your three-and-a-half-year old. It can be the ragged handful of wildflowers from your seven-year-old or the joyous exclamation, “This is the best birthday EVER!”

Children do not simply take; they receive, and they reciprocate, often in ways that are more natural, organic, and blunt than adults. These are the moments that you must hold onto . . . because these are the moments that the voice of depression tries to blur into obscurity.

For most of us, the voice begins to whisper when we’re sleep-deprived, getting sick, lacking basic self-care, or going through relationship turmoil. The ironic thing is how convincing the voice is when it only ever murmurs variations on the same theme: You are worthless . . . no matter how hard you try, you always end up here . . . no one wants you . . . you have nothing to offer . . . nothing you ever do matters . . . you’ve never made a difference . . . it would be better if you were never born.

The voice lies with fluid and seamless improvisation, adapting itself to every new scenario or opportunity that arises. It is an expert at situational awareness, professionally masquerading itself according to setting, theme, and character development. It is clever and quick, but not truly intelligent–because it speaks without balance, and, ultimately, it never has anything new to say.

Religious believers will tell you that the voice of depression is the voice of demonic persuasion and to shut it out at all costs. Psychiatrists will tell you the voice of depression is symptomatic of a chemical imbalance in the brain and may prescribe Prozac or Zoloft in an attempt to silence it.

I think the voice of depression is so convincing because it speaks directly to the terrified child that still lives inside of every adult—the child imprisoned by fear of abandonment, isolation, starvation, and emptiness. The voice tells that child that all of his worst fears are coming true: that no matter how evolved, accomplished, successful, or loved the adult has become, the child inside of him will always be unloved and unworthy. This is the genius behind the voice of depression.

This is what makes the voice such a formidable nemesis.

The voice speaks to the existential crisis of every human child. Unlike most mammal newborns, humans are born totally incapable of survival without dependence upon a caretaker. In other words, they need to be loved to survive. Even orphans given the basic necessities of life (food, water, shelter) will succumb to failure to thrive without love. Love is what defines our humanity more deeply than any other characteristic, and love is what the voice of depression tries to erase, condemn, or obfuscate–at all costs.

When we are infants, we die without love. When we are adults, we want to take our own lives if we feel love has abandoned us. As parents, we watch our children experience meltdown after meltdown as they encounter the boundaries, limitations, and enforced balance of human existence. And when we lose our tempers because of one too many meltdowns or feeling the same boundary pushed one too many times, we can make our children encounter their worst fear: the fear of being abandoned by their parents—of losing the love upon which their survival depends.

When I put it this way, it seems I am guilting myself and every other parent in existence for the eminently reasonable and utterly inevitable reality of losing control. All I can speak to is my own experience and observations, and for me, guilt exists as a method of self-regulation to help us process that we can and should do better next time.

I believe that parental guilt is fundamentally unavoidable—that it exists, in fact, to keep our children alive. I believe it’s better to be real with ourselves about our own limitations than to make excuse after excuse about why our anger is justified. And I believe the voice of depression speaks loudest to parents as a result of that guilt . . . and the requisite shame of knowing that we can and should have done better by our children.

Losing our tempers with our children triggers the existential fear of every child, which, in turn, triggers a chain reaction of existential fear in ourselves and those closest to us. It can take hours to set up a train of dominoes and only minutes to watch them all fall once the first one loses its balance.

It’s not fair to have so much rely upon our mental, emotional, and physical stability. It’s terrifying to feel that the survival and happiness of multiple little people is dependent upon our ability to keep ourselves functional. It requires a superhuman level of equilibrium and no small amount of sheer luck to ensure that the internal and external environments in which ourselves and our families are immersed stays peaceful, calm, and balanced. Too few parents experience such optimal conditions for parenting.

So, when it comes down to it, parenting is impossible, right? No one parent can be perfectly and proportionately responsive to the needs of her child (more or less multiple children) 100% of the time. We need to make time for self-care and retain our own identities before, within, and beyond who we are as parents. We need to have things for ourselves and take time away from our children occasionally, right? We need feel comfortable asking for help. We need to do whatever it takes to maintain balance.

- In the United States, more than 600,000 children are abused every year.

- Children in the first year of their life are 15% of all victims.

- In 2020, an estimated 1,750 children died from abuse and neglect.

- In substantiated child abuse cases, 77% of children were victimized by a parent.

- More than 75% of victims were neglected; 16% were physically abused; 9% were sexually abused, and 0.2% are sex trafficked.

For any parent, those statistics are hard to read. This is not because most of us are guilty of child abuse or neglect, but rather because we have intimately encountered the emotions in ourselves that could lead a parent to abuse or neglect a child. For those parents who struggle with severe addiction or whose socio-economic situation is ever-stagnating in a self-defeating loop, it is even harder to fight the tendencies towards abuse or neglect.

In the animal world, offspring require resources. If resources are not available, survival kicks in, and many animals kill or eat their young.

We are not animals; or, at least, most will agree we are evolved animals. But the rules of survival and resources still apply to us. In nature, females are attracted to males that demonstrate the characteristics most optimal for survival and genetic propagation. They choose the males that can sire strong offspring less likely to die and who can provide the resources needed to raise those young to maturity. If danger or deprivation changes the situation, the young can all too easily be abandoned or killed.

Anyone who has watched a David Attenborough nature documentary knows these things to be true. We like to draw sharp distinctions and blur the similarities between ourselves and other animals, but the basic rules of biology still apply. And, to complicate matters, human animals are capable of intentional cruelty, self-injury, substance abuse, and severe mental illness.

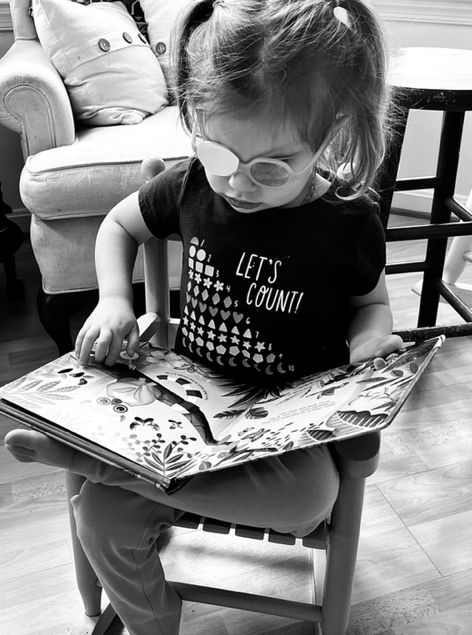

All toddlers are hard. But, sometimes, I feel absolutely terrified that my second daughter inherited my rebelliousness, my stubbornness and my pride altogether. These days, she responds to any request with “No!”, followed in one-to-sixty-second intervals by, “I can [fill in whatever you’re asking her to do].” We’re trying to change this behavior to “Okay, Mom” or “Yes, sir, Dad”. Part of the task is reprogramming her little brain to a new routine; the harder part is helping her feel in control of consent without saying “no” first.

Lately, I’ve been trying to get off the emotional roller coaster and guilt spiral of disciplining my daughter. Last week, I placed her calmly in her room, finished cleaning the kitchen, waited for the screaming to die down, and then returned ten minutes later to sit down quietly on her bed.

“Hi, Mom,” she said.

“Hello,” I responded.

“I can say ‘yes ma’am, okay Mom.’”

“Yes, you can. You’re a big girl.”

“Do you want to have a hug?” she asked, sure of my response.

“I would love to have a hug.”

And she toddles over to me, reaching her arms up and asking brokenly, “Mama get you up-up. Mama hold you?”

“Yes, Mama can hold you, baby. Mama loves you very much.”

When I first started disciplining my daughter, I felt like I was breaking her trust and breaking her heart along with it. It became more and more clear with time that boundaries and limitations were good for her. I could hear the rage and terror of abandonment in her voice with every meltdown. But ten or twenty minutes later, after I had repaired the breach, I found her to be sweeter and happier than before, content in the knowledge that she had expressed her feelings and been forgiven; she had done what was asked of her and made me happy.

She had encountered a boundary to her existence, and it made her feel safe.

Our job as parents is to convince our children that the world is not sheer, ungovernable chaos. We must propagate the fantasy that we have navigated the world and mapped its dimensions, limitations, and regulations. We have charted the fathomless seas wherein monsters dwell and can pass on the secrets of our captainship.

The younger our children are, the more critical it is to hide our own fear and acknowledgement that we don’t have all the answers. As they grow, we can gradually become more truthful, passing on the terrible reality that we aren’t in control of most things and teaching them how to swallow mystery in parts per million–small enough to digest–small enough to resist infection.

I believe that parenting is the hardest thing most of us will ever do.

Parenting forces us to encounter the worst parts of ourselves, parts that are so much easier to hide when self-care and self-provision are our only occupations. Parenting strips the pretense from our personalities that we have it all figured out. It exposes the naked dread in our children when the calm, confident god or goddess that is Dad or Mom cracks, disintegrates, or explodes, revealing the slathering monster within. It transforms us into superhumans and reduces us to subhuman in quick succession, sometimes so rapidly that it leaves our heads spinning.

Parenting makes us more vulnerable to the voice of depression because it requires too much of us all the time.

This simultaneous too much and not enough of parenting is what makes it impossible. What is necessary is to redefine for ourselves the horizon of the possible. Is it possible to parent without losing our tempers or equilibrium, frightening our children or ourselves, or feeling like we are perpetually failing?

No, at least not in this world.

But it is possible to rebuild trust and relationship. It is possible to admit our failings and reveal our manifold imperfections piece by piece, so that our children still feel they can rely on us to help them through their small crises. It is possible not to vacillate between extremes of goddess and devourer and to strive towards a balance where the world that we create for our children is bounded by limitations that both frustrate them and keep them alive.

It is both possible and impossible. It is parenting.

The voice of depression cannot speak the truth.

It has only access to twisted truths and tangled versions of reality. There is always a bigger truth and a greater reality behind the chronicle of events narrated by the voice of depression.

The struggle is to find your way back once the voice starts speaking… because the longer it speaks and the more stage you provide, the harder it is to exit the theater.

So, the next time the voice starts whispering to you, call it out. Shine a flashlight and cut through its shadows. And if you can’t find a flashlight, close your eyes and take a nap. When you wake up, have a snack. Take a break or ask for help. Walk outside and force yourself to listen to birdsong or feel the sunlight on your bare skin. Google orphans who scrape existence from mountains of trash. Watch your favorite movie. Plan a date night with your spouse. Eat some ice cream and try to laugh.

And, if you can manage it, hold your child in your lap and sing your favorite songs to her or read him your favorite book. Hug him or kiss her little cheek and let it be okay that you are, for this moment, something, even if you cannot be everything.

Whatever you choose to do, try not to speak to the voice. Above all, don’t let the voice speak for you. It cannot and will not help you feel better for giving it airtime. All it is capable of is lies.

And its greatest lie is that if you let it speak, you will achieve release or effect change. It cannot do either. It has only the ability to harm. If possible, contain the harm to yourself, rather than releasing it on your spouse, your children, or even the poor telemarketer on the other line.

Darkness, cruelty, and blame have only the power to make things worse. And they can accomplish this surprisingly quickly. It’s the small and simple things, the things that take time to build, and the things that are easily destroyed that are the most beautiful. Flowers in springtime. The taste of fresh strawberries. The feel of your newborn’s fingers clasping your thumb for the first time. Patience. Endurance.

Hope.

I do not think there is any way to permanently silence the voice of depression. I think the only thing that can is death. The key is instead to find a way to not play into it. To do the things that shut it down and shut it out and to get more adept and efficient at these things as time goes on.

Depression is real, but it can also be a choice–a choice that we must strive not to make, for our own sakes, the sakes of our spouses, and, especially, the sakes of our children.

After all, the job of parenting doesn’t stop just because you feel like you can no longer parent.

“If you can’t fly, then run; if you can’t run, then walk; if you can’t walk, then crawl, but whatever you do, you have to keep moving forward.”

– Martin Luther King, Jr.

Take it one breath at a time, one minute at a time.

Remember not to forget yourself.

Drag yourself into that standing position, even if you have to use a chair to do it.

Understand that grace comes with the years, with mistakes, and with endless sorrows.

Sorrow. Grieve.

Feel shame if you must.

Let the guilt wash through you.

Ride the wave to its crest, then let it fall, and let it fade.

Forgive yourself.

Your children already have.