Top 5 Parenting Rules (that I break all the time)

No parent has it all figured out, and most of us need more than a little help every once in a while to keep our heads above water. In our newly blended family, we struggle to cope with the complex dynamics involved in step-parenting, adopted parenting, newborn parenting, and parenting a child with a serious medical condition. It’s tough to juggle everything without feeling like you’re letting some of the balls drop.

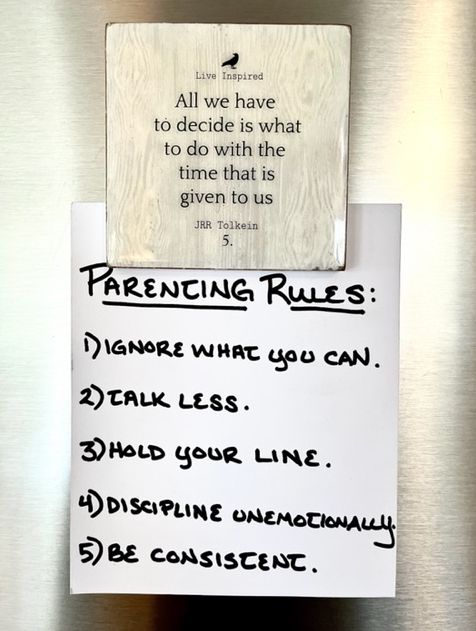

I’ve tried to take to heart the advice of my father and my mother-in-law, both of whom are deep wells of parenting wisdom. I’ve thought for weeks about how to distill the most relevant suggestions from each of them. Finally, I drafted 5 seemingly simple (but difficult-to-implement) rules for parenting and posted them on our fridge, where they would be immediately available for reference in a moment of stress.

Here’s a quick breakdown of each rule.

Rule #1: Ignore what you can.

My mother-in-law’s version of this is “pick your battles.”

Children are little scientists, constantly engaged in conducting experiments to determine the limits and boundaries of the world surrounding them. They are bound to do things inefficiently and improperly. It’s hard to gauge when to step in and offer help and correction and when to take a backseat.

Because children are constantly testing boundaries, they are likely to obsessively fixate on pressing against an established boundary (i.e. a house rule) to test for weaknesses and see where pushing elicits a parental response (either positive or negative). My husband, Peter, and I joke that they’re like raptors testing for weak points in the electric fence.

We want to make life as black and white for ourselves and our children as we can, but the truth is that the older you grow, the more you understand exactly how complex life is. We can give our child a clear-cut boundary, but there’s usually much more involved in maintaining and abiding by that boundary.

With time, I began to expect that our children will push the boundaries we’ve established. By ignoring the majority of what’s being pushed, I allow them the freedom and autonomy to experiment with limitations. By only stepping in when I feel it’s actually necessary, I help to concretize in their mind what the boundary is.

It is neither necessary nor necessarily beneficial for children for their every choice or action to be magnified or corrected. They are going to do things that you don’t like. The question is whether or not you don’t like those things enough to intervene.

Another way to implement this rule is to ignore behavior you don’t like (within reason) and calmly respond to behavior you do like. Most children want attention from their parents, whether positive or negative. Positive attention to good behavior helps condition good behavior; negative attention to bad behavior can condition bad behavior.

Rule #2: Talk Less

Talking too much can get us all into trouble. We all could benefit from talking less, but I find that talking less while parenting results in pretty much nothing but a net gain for everyone.

Talking to someone implies a desired response. Talking therefore requires an engagement. Children can get very wrapped up in anxiety over how to give the parent the correct verbal response.

The best book I have read on parenting is called The Science of Parenting by Margot Sunderland. It gives an excellent overview of what current brain science tells us is occurring in the minds of children. I highly recommend reading this book, but I’ll give a quick summary of what it says about the reptilian, mammalian, and human brain development in children.

As evidenced by the infant, children begin as nonverbal creatures. Children are born with a basic reptilian brain that acts out of instinct, optimizing survival. The mammalian parts of the brain are also partially developed in newborns and infants. Throughout childhood, the mammalian brain, which controls emotion and intuition, is developing. The neocortex, or human brain, capable of reason, logic, and empathy, does not begin to develop until adolescence and beyond.

Children are thus very much creatures of emotion and instinct. Again, as evidenced by the infant and toddler, children learn best through watching and listening. They naturally mimic behavior and language. The more that we, as parents, can model the behavior we desire from our children, the more we are setting up ourselves and our children for success.

Talking too much can produce anxiety in both adults and children. The less we say, the more our children can focus on what we do say. The more we model the verbal patterns we seek from our children, the more they are likely to mimic those words. The more we take a deep breath and choose our words carefully, the more likely we are to maintain equilibrium and avoid the guilt spiral.

There is so much to say about this rule, and I have written elsewhere about the value of silence. Talking can sometimes cost so much time and so much mental and emotional energy; it can even cost trust or confidence in yourself or in others. Actions speak louder than words, and if we allowed our actions to speak more than our mouths, we might find the process of becoming just a little bit easier–for both ourselves and our children.

Another way of implementing this rule is to calmly say, “No, thank you,” or “No, sir,” and then immediately disengage. Instead of entering into a verbal battle or detailed explanation of why the behavior is wrong, simply correct the behavior, then return to what you were doing.

Children will seek out any form of attention from their parents, positive or negative. Talking less helps curb the negative attention spiral where the child will continue the behavior that gained the parent’s attention. Instead, warmly and calmly praise or encourage behavior that you do like, and engage as little as possible over behavior that you don’t like.

Rule #3: Hold Your Line

Me: ****word vomit****emotional spiral****frustrated tears****

Peter: “Decide what you are going to give ahead of time; don’t give more; don’t give less.”

Parents instinctually give everything to their children: care, shelter, food, drink, love, affection, time, energy, attention. What children have to offer in response is much harder to define and measure: wonder, delight, fulfillment, meaning.

Love.

Similar to a fetus in utero, who will take from the mother what is needed for proper development, children will instinctually take and take and take and take. Without attention to self-care and balance, a parent can rapidly become drained. And when life is complicated and children have traumatic histories, the need for care and attention can be like a hunger that is never satisfied.

The best thing to do is to pull back from the emotion, take some space, and only when you are fully rested, satiated, and comfortable, determine for yourself what level of care and attention you believe is best to give your children each day.

You are the expert on your child. You know his or her needs and wants inside out. You are in the best position to determine what is healthiest mentally, physically, emotionally, and developmentally for your child. But your capacity for determination is limited if you are lacking self-care or if your decisions are influenced by your own guilt or pressure from your child.

Children need boundaries. Adults need to draw their own boundaries with children. Very few boundaries need to be drawn with infants; the older a child becomes, the more important boundaries between the child and the parent become.

The best way of implementing this rule is to decide ahead of time what you are going to give to your child in terms of energy, time, care, and attention. Then, hold your line by not giving more and not giving less. This way, you protect both yourself and your child from the physical and mental breakdown that will come if your child continues to take or require more from you than you are capable of giving.

Rule #4: Discipline Unemotionally

I find all of these rules hard to implement, but this one is the hardest. I’m also ashamed to admit that this one is much harder with my stepson than it is with my daughters, both of whom are biologically mine.

As a woman, it is more intuitive for me to be gentle and to discipline unemotionally with toddlers and babies. I tend to perceive older children as being more aware of the choices they are making and therefore more responsible for their choices. But moral culpability in children is a very complex topic, and it has taken me time to accept that even older children are more often acting out of impulse than intention.

With my 2 living daughters, currently ages (almost) 4 years and (almost) 5 months old, I tend to rely on the strength of the relationship to carry me through stressful moments that require discipline. My daughters’ desire to please me is so strong that they immediately attempt to fulfill the behavior I am seeking. As a result, the conflict tends to be quickly and painlessly resolved.

My relationship with my stepson, however, did not begin until he was 6 years old. As a result, neither of us can fall back on the relationship to carry us through moments requiring discipline, which occur far more frequently with a bright and active 7-year-old boy than they do with the girls.

It’s hard–so very hard–not to take things personally. And it’s even harder when there are step-relationships involved. But it’s also more necessary.

I have struggled with feelings of shame and guilt for most of my adult life. I’m very familiar with their patterns of dialogue. Together, they can be so mentally crippling that they incapacitate all action.

They have no place in a child’s life.

Disciplining unemotionally makes the discipline impersonal. It makes it about the action–not the child. It makes it about the boundary–not the parent. It simply and cleanly establishes the supremacy of the rule that has been broken.

I find the most effective form of discipline is to remove the child from the situation. This can be implemented in a variety of ways from time out in a bedroom or facing a corner, to chores, to writing “I will try harder to listen and obey” ten times in a notebook.

Children naturally have a short attention span, so you are often experiencing the emotional fallout of the situation for far longer than they are. I’ve been trying to give myself and them a break by taking as much emotion out of the consequence as possible.

Rule #5: Be Consistent

Forming healthy habits and building healthy routines is beneficial for every human person, regardless of age. However, with children, routine and consistency is not just healthy; it’s imperative for secure emotional and psychological development.

For every person, the process of maturation includes coming up against unpredictable violence, the irrationality of evil, the terror of the unknown: the sheer chaos that exists in the natural world and in the depths of the human heart. Historically, human beings have striven for order precisely to make some sense of the chaos surrounding us.

It is my belief that part of the job of being a parent is helping your child believe in the illusion that you, as the parent, comprehend the workings of the world and are in control–at least of the most immediate things. As the child matures, you can reveal to him or her piece by piece exactly how enormous, overwhelming, and terrifying the world can be. You can begin to discuss things like the Holocaust or the genocide in Rwanda.

But the younger the child is, the more important it is for the child to feel that his or her parents stand in between the child and utter chaos or total annihilation.

This is why, in my opinion, it is so important for parents to be consistent.

Consistency and predictability give order, meaning, and structure to a world that would otherwise be absolute anarchy for a child. One of the worst things that we can do as parents is to vacillate between a Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde personality while parenting. The child is unable to determine what does or does not cause the monster to appear, and that fundamental fear and insecurity begins to rule the child’s consciousness.

Consistency protects both parent and child from abusive, destabilizing, and anxiety-promoting patterns. It protects the mental health of both parent and child.

If the child breaks a rule, the child undergoes discipline/consequences for breaking that rule. The more consistent a parent is at following through with consequences, the quicker the child learns what happens when he or she breaks the rule.

It’s the process of charting and navigating the vast unknown into which the child is born. The parent is helping the child to define his or her boundaries, determine his or her limits, and gauge where danger and safety lie. The more consistency present in this process, the faster the child learns, the safer the child feels, and the more secure he or she is in relationship with the parent.

Consistency is a parent’s responsibility.

This can feel overwhelming, especially when you want to switch things up because you feel they haven’t been working. It can be the right decision to troubleshoot and change discipline tactics or rules when you feel it’s necessary. However, doing this too often can put cracks in the foundation you are trying to build.

Your child needs to believe that you know what you are doing, and you are in control. Your child is not mentally or emotionally ready for the reality of how limited human control actually is.

Help your child to believe in you by believing in yourself. Belief has the power to transform realities.

Obeying My Own Rules

All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.

J.R.R. Tolkien

I very intentionally placed my write-up of these rules beneath my favorite quote because I wanted to remind myself in times of trial that my choices, every single day, impact the comprehensive wellbeing of the little lives that have been entrusted to me.

I’d like to say that I’m getting better at obeying my own rules, but the reality is that I still struggle. I struggle every day. I want to be better than I am, and so I promise myself I will try harder tomorrow. Some days, I’m strong enough to keep that promise.

Some days, I need to remind myself. So I go through my rules, one by one:

Ignore the behavior you don’t like, and calmly encourage the behavior you do like. Talk less during routine activity and discipline. Decide ahead of time what I will and will not give, then hold that boundary. When discipline is necessary, do it without emotion. Above all, be consistent in routine and discipline, in kindness and affection.

Create boundaries, then hold those boundaries as wave after wave crash against them. Let the children wade in a tidepool before swimming in the ocean. And if you feel your boundaries washing away with the waves, build them back up.

Make the most of the time that is given to you. It’s all you really have.