Medical Play Therapy: a Case Study

October 10, 2022

The room was dim, muted, oppressive. The slight whir and buzz of the radiology equipment dominated all human interaction. The technician moved dully about her business, inputting data, prepping for the ultrasound. We were there for information; she was there to obtain it.

I leaned to once more embrace a 3-year-old Cecilia, asking quietly, “Can you lay down for Mommy, baby? We need to look at your little tummy.”

Whimpering, but still secure in my touch, Cece tried to comply, laying down inch by inch on the hospital bed. The technician briskly moved to tuck a towel into the front of Cece’s pants, pulling them down slightly, and gibbering in a half-baby-voice to Cece about what she was doing.

Cece’s whimpering turned into moaning, followed by crying. Trying to stem the tide of panic, I moved next to her, trying to adjust the towel, allow her to feel it, explain that the lady was going to take pictures of her tummy. But it was already too late. The touch of the stranger had consumed her consciousness, and Cece could no longer trust me to protect her.

She started to thrash and push away the ultrasound wand, reaching down to feel the gel, then crying in incomprehension. The technician asked me to hold her still. I applied some of my weight, grasping Cece’s hands, holding and murmuring to her that everything was okay; it was just pictures; she didn’t need to be afraid. As usual, my reassurance had the opposite effect, my voice and words gave lie to the reality that I was holding her down so that a stranger could touch her. Her cries escalated.

I breathed deeply, continuing to whisper meaningless assurances, continuing to hold her. My husband, Peter, stood behind us, watching in helpless horror while Cece’s fear bled out, her screams consuming the room. Her baby sister stirred in my womb, as though disturbed by all the noise. I tried to focus, to regain control. I tried to tell Cece that it didn’t hurt; it was just an ultrasound.

It was just what the nephrologist ordered.

The technician suggested we place Cece in a restraint. I asked to see what she was referencing. It was a sort of child-sized straightjacket with an open middle. It would stop her from thrashing so they could get the images.

Numbly, I agreed.

We tried to strap Cece into the restraint. Peter took one half of her body; I took the other, and the technician tried to apply pressure on her lower half to keep her torso accessible. Cece was screaming so constantly that her face was turning blue from lack of oxygen. Tears were streaming out of the corners of her eyes, and her mouth seemed frozen in a rictus of terror. She was living in a nightmare, screaming again and again: “Want to get down, want to get down, please get down!”

I said to the technician, “Please, we need to give her a break. Can you please just wait for a minute and let her get down?”

In mild irritation, the technician agreed, unable to conceal her surprise and accusation that our over-dramatic toddler couldn’t handle a procedure as painless and simple as an ultrasound.

Released from her constraints, Cece scrambled off the bed, falling the last foot to tumble across the filthy hospital floor. She stumbled to her feet, sobbing, “Mommy, Mommy?”

“I’m right here, big girl,” I said, brokenly, trying to guide her faltering steps with my voice. She turned towards me, glasses askew, searching for me, and I stepped towards her and swooped her into my arms, trying to communicate without words that nothing bad was happening; she wasn’t in any danger; we were doing this to help her.

Visions began to tumble through my mind, too fast to order or describe. An 8-month old Cecilia with impossibly thin copper wires placed inside her bottom eyelids, screaming into the helmet that was flashing lights at her, trying to measure and define for us exactly how unresponsive her retina were. An 18-month-old Cecilia kicking and screaming as NIH nurses attempted to wrench open her eyes to place drops in them to dilate her pupils for examination. A 2 1/2-year-old Cecilia sobbing heartbrokenly, nearly unable to breathe, trying to take off a blood-pressure cuff while nurses applied more pressure, holding a iPhone blasting an “Old MacDonald” YouTube video in front of her blurred and unseeing eyes.

Cecilia was burying her face into my chest, but her gasping and sobbing wasn’t quieting. Still screaming, she wriggled out of my arms onto the floor, and then stumbling in the opposite direction, gasped in her staggering little voice: “Dad-dy. . . ? Dad-dy?”

His face a mask of anguish, Peter stepped to swoop her into his arms, his entire body radiating rage and grief at his absolute inability to help. She tried desperately to burrow into his armpit before scrambling back out of his arms and stumbling again towards me.

I reached to pick her up, but like a wild animal unable to find sanctuary, she turned from me, eyes still streaming tears, back towards Peter. He picked her up again, muttering inarticulate noises to soothe her, and, gradually, her sobbing began to quiet. I turned away to hide my own tears, drowning in my own grief and indecision.

Knowing how important it was to Cece to initiate anything that happened to her, Peter said quietly, “Would you like to do your ultrasound now, big girl?”

Slightly hiccupping, Cece responded, “I can do my ultrasound, Dad.”

“You can do it, big girl.”

“I can do it, Dad.”

With infinite gentleness, he placed her back on the hospital bed and pulled up her shirt, motioning to the technician that she needed to stay silent, please. Her little body shaking, Cece allowed Peter to pull down her pants enough to tuck in the towel, then held her little hand secure in his own, pressing a kiss to it, murmuring to her that she was being such a good, big girl.

The technician squeezed ultrasound gel on her wand once more and pressed it against Cece’s abdomen. Like a dam breaking, Cece’s face crumpled and fell, an animal-like sob of pain and fear escaping from her red and chapped little lips.

“No, no, no, no, no,” Cece repeated mindlessly, shaking her head back and forth, trying to squirm away from the wand, trying to wrench her hand from Peter’s grasp.

I looked from Peter’s white and stricken face to Cecilia’s purple and betrayed one. Then I looked the ultrasound technician in the eyes and said firmly, “I can’t keep doing this to her. We’re done.”

Cecilia’s story

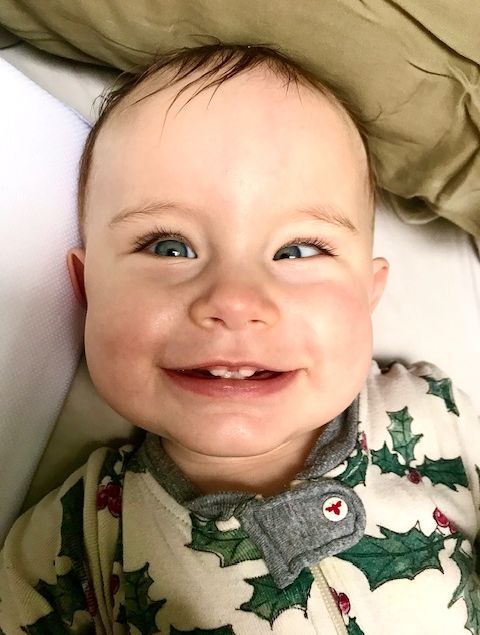

Our daughter, Cecilia, was born with a one-in-a-million worldwide genetic disorder that causes blindness and kidney disease. From 4 months of age, Cecilia’s short life has consisted of an endless string of doctors, nurses, technicians, and therapists. All of these people are just trying to do their jobs and trying to help.

As true as this is, it is also true that the constant intervention from the medical world has created within Cecilia intense fear, anxiety, mistrust, and an obsessive compulsion to initiate even the smallest thing before it happens to her.

Her condition is degenerative over a long period of time; there are no interventions that have been done on Cecilia to date that have helped her either to live longer or to improve her quality of life. Being prescribed with glasses remains the only medical intervention that has tangibly helped Cecilia in any way.

Everything else simply is what it is: data with a time stamp.

my choices

My guilt surrounding the choices I have made for Cecilia has been intense and absolutely crippling at times. Because she was born 1 month after the sudden and unexpected death of her 2-year-old big sister, I was still in shock, grieving, and traumatized throughout the process of her diagnosis. I didn’t trust myself and thus surrendered myself and Cecilia fully into the medical world in a desire to simply keep her alive.

I would not make the same choices today.

Everything in human life is a risk versus benefit equation. Riding in a car entails a massive risk to human life that most of us undergo daily without thinking much about it. Four years ago, I was so desperate to keep Cecilia alive that I was willing to subject her to test after test, procedure after procedure.

She’s still alive. She turned 4 years old in May. But she’s not better off for all these tests and procedures.

mental health

Today, Cecilia’s mental health is my main priority. This doesn’t mean that I will not remain vigilant to watching for symptoms of kidney disease onset or continue to take her to the ophthalmologist to get her new glasses as her prescription changes throughout the years. It only means that I intend to control how frequent and how invasive the medical world is in managing my daughter’s disease.

As I mentioned above, Cecilia has been thoroughly traumatized by routine medical procedures since she was 4 months old. Her trust in me as her mother to protect her has been broken again and again. Believing that I was doing the necessary thing to “help” her, I have forcibly held her down many times while strangers that she couldn’t see did things to her body that she didn’t like and didn’t understand.

A 4-year-old cannot rationalize this betrayal anymore than a 1-year-old.

For Cecilia’s entire life, I have been in and out of the best children’s hospitals on the east coast, and I have watched the faces of parents wheeling their children in and out of emergency rooms and pediatric intensive care units. I am intensely grateful that my daughter’s disease is slow to progress, degenerative over time, and has placed her life in no immediate danger.

This is not the story for every parent.

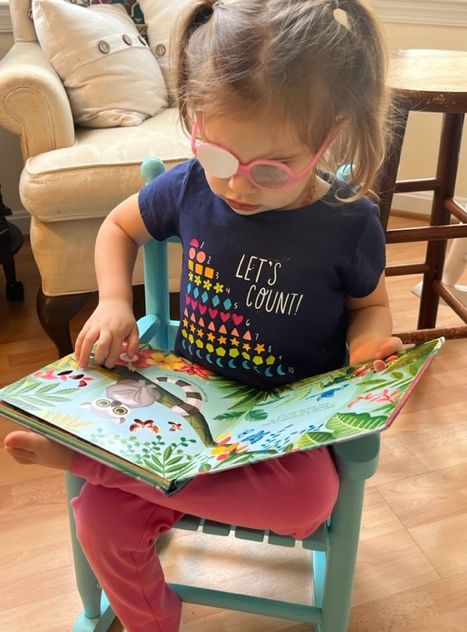

Because Cecilia’s physical health is not in immediate jeopardy, I have the ability to prioritize her mental health. I will take the time needed to rebuild her trust in her parents to protect her. I have the patience to wait day after day as she pauses, delays, prompts, questions, spins in loops, hyper-fixates, panics, spirals, melts down, calms down, repeats, and, finally, re-initiates.

Because I made choices for her that she still does not understand, I will bear the pain, the time, the energy, and the exhaustion it takes to help her process the world surrounding her and begin to understand her lack of sight, her life, and her body.

patience

Patience is not something we learn in American culture, as evidenced by our tendency to either compartmentalize or plug in our children. But patience is the thing that we need most as parents, and patience is the thing that Cecilia has taught me above all else.

Most children who are visually impaired are intensely pattern-driven and have trouble adapting to changes in routine. Cecilia is no exception to this. She can neither understand nor respond as quickly as the other members of our family, and, as a result, there is always a delay that requires extra time and patience in order for her to comply without a meltdown.

Cecilia has obsessive tendencies regarding chronology and often repeats words again and again trying to obtain the proper response that helps her understand the formula behind what is occurring. Often, she refuses to do what she is being asked simply in order to buy herself time to understand what is being asked. For example:

Me: “Cecilia, can you please get into your seat to have some breakfast?”

Cece: “No; no, thank you.”

Me: “Yes, ma’am, okay Mom.”

Cece: “I can say it!”

Me: “Yes, you can.”

Cece: “I can say it!”

Me: “You can say it.”

Cece: “Yes, ma’am, okay Mom. I can get into my seat to have some breakfast.”

She requires this call-and-response pattern in order to move forward. If she doesn’t receive it, she can be stuck in the same mental place for hours.

Needless to say, this can be exhausting for any adult acting as her primary caretaker. Her 7-year-old big brother can’t comprehend why it takes Cece so long to do simple things and just accepts that this is how Cece is.

Our family has adapted to her patterns, routines, and need for call-and-response. But the world outside our home is vast, overwhelming, and filled with people trying to move from one thing to the next.

Knowing this, Peter and I worked the past few weeks to prepare Cecilia for everything that would happen during her most recent hospital visit. We used a method called play therapy to prepare her for every procedure that would happen at the hospital, and it was successful . . . beyond our wildest dreams.

medical advice disclaimer: This website does not provide medical advice and is intended for informational purposes only. Any statements or claims about the possible health benefits conferred by any foods or supplements have not been evaluated by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and are not intended to diagnose, treat, prevent or cure any disease.

affiliate disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links. See my full affiliate disclosure for more information.

medical play therapy

The National Association for Play Therapy defines “play therapy” as:

the systematic use of a theoretical model to establish an interpersonal process wherein trained play therapists use the therapeutic powers of play to help clients prevent or resolve psychosocial difficulties and achieve optimal growth and development.

I’ve read widely about play therapy, but it was Peter who took to it like a fish to water. He’s intuitively better with children than I am, and he needed very few explanations to understand the concept and utilize it.

My method typically involves giving myself and Cece the space, environment, and time to allow her to understand and process what needs to happen. I allow her to feel what is happening, then ask her tell me when she’s ready, then count to 3. Peter’s method is to make a game out of it and use stuffed animals to demonstrate.

eye drops

During trips to the ophthalmologist, Cece’s eyes need to be dilated with atropine drops for examinations, tests, and pictures.

history

Cece is usually playful and responsive during eye exams and even cooperative during opthalmalogy pictures. By far, the worst part of eye exams is when we’re handed from the doctor to the nurses for eye drops. It typically involves Cece screaming uncontrollably while we try to hold her still and wrench open her eye lids for the drops. It can take Cece up to an hour to calm down after this, and sometimes, she will refuse to touch me or allow me to hold her.

materials

- 1 stuffed animal

- 1 small bottle of saline solution

method

We started practicing eye drops with saline solution about a month before our visit. The first time, I asked her to lay down and allowed her to feel the small bottle of saline solution. I then asked her if she wanted to do her “eye drops” and she giggled and said, “yes, please.”

I counted to 3, then put a small drop in her eye. She half-laughed, half-cried, and I praised her, telling her she was such a big girl. I then allowed her to feel the bottle again before repeating the procedure with the other eye. When we were done, she asked if she could do it by herself, and I allowed her to take the drops, count to 3, and shake them in her own eyes.

Peter took everything a step further by using one of Cece’s many stuffed animals and modeling what he was seeking from Cece with a silly voice. This method was so effective that he could even get Cece to hold open her own eye for the drops.

Peter: “Would you like to do your eye drops, Peter Rabbit?”

Peter as Peter Rabbit: “Yes, please! I would love to do my eye drops!”

Peter: “Okay, lay down and we’ll count to 3! 1 . . .2 . . .3. . .” [pretends to squeeze a drop]

Peter as Peter Rabbit: “Oh my! How fun! That eye drop felt so nice and cool! Would you like to do your eye drops, Cece?”

Cece: “Yes, please!”

why this works

This method of modeling the behavior with stuffed animals allows the tension and pressure to be taken off of Cece while everyone pays attention to the stuffed animal demonstration. Cece has time to process what is being asked of her and builds desire to participate in the game. By making a game of it, the trauma of the actual drops is reduced greatly and she receives praise for playing the game rather than needing comfort post-meltdown.

results

I exchanged several messages with her ophthalmologist leading up to her visit about desiring to do the drops myself, preferably ahead of time. He agreed and suggested I do them twice: once the night before the visit and once the morning of the visit.

Peter used Peter Rabbit to model the drops and Cece cried slightly since the atropine drops felt different than the saline but she smiled and laughed immediately when Peter Rabbit congratulated her. She held open her own eye the morning of our visit and was very proud of herself for doing her drops.

This was, by far, the most painless experience of atropine drops we have had to date.

ultrasound

Since her diagnosis, the nephrologists have ordered multiple ultrasounds to assess the size, location, and shape of Cecilia’s kidneys and measure her urine output.

history

We have attempted a total of 3 ultrasounds. The first one was performed when she was less than a year old, during which I sang her favorite songs nonstop and repeatedly attempted to prevent her from pushing away the ultrasound wand. The second is described at the beginning of this post. Because of play therapy, the third was an absolute success.

materials

- 1 stuffed animal

- 1 old dishtowel

- 1 small bottle of aloe vera gel

- 1 toy that feels like an ultrasound wand (we used the plastic end of a toy microphone)

method

We started practicing ultrasounds with Cece about 3 weeks before her hospital visit. I asked her if she wanted to do an ultrasound, and assuming it was a new game, she said, “yes, please.” I asked her to lay down, then allowed her to feel the dishtowel and told her I was going to tuck it into the front of her pants. I then asked her if she wanted to feel the gel and allowed her to hold the closed container.

I told her I was going to squeeze the gel onto the ultrasound wand and press it against her little tummy. She giggled the first time I did this, then whined and asked if she could hold it. I allowed her to hold the toy microphone and feel the gel on the toy and on her belly. She asked if she could do it by herself, and I allowed this as well.

Peter trained her to hold a different stuffed animal with each practice session. While he was moving the “wand” across her belly, occasionally adding gel, he would ask her to point to her eyes, ears, nose, mouth, the top of her head, etc. Sometimes, he would ask her to listen to her baby sister playing next to her bed or her service dog, Luthien, rolling around on the floor. Other times, he would play her stories on her talking book machine.

Occasionally, I would read a book of bedtime poems to her and she would hold my hand or Peter’s hand or both. We gradually increased the time of doing the ultrasound practice until we reached about 20 minutes. We practiced at different times of the day in different locations to switch up the routine so that she could adapt to the circumstances that would be present during the actual ultrasound.

why this works

Cecilia learned to love her ultrasound practice so much that she would ask for an ultrasound every day before quiet time. She valued the one-on-one time with Mom or Dad (or both) and loved listening to her stories and playing with her stuffed animals. Making it a familiar and fun part of her every day routine helped strip the process of its strangeness and fear. Pairing the uncomfortable sensation of constant pressure on her abdomen with her stories and stuffed animals allowed her to process the experience as similar to or familiar as a bath or being strapped in and out of her car seat.

results

Cece was obedient, calm, and peaceful throughout the entire ultrasound, which lasted approximately 40 minutes. Peter allowed her to hold one of her stuffed animals, Tiger, throughout the process. He read the entire book of Goodnight Songs Treasury by Margaret Wise Brown to her and held her hand. She wasn’t scared, anxious, or upset even once. I walked around with her baby sister in the Ergobaby and engaged with the technician when necessary.

Cece managed effortlessly when the technician needed her to roll from side to side to access different parts of her kidneys. There was no panic or fear, as everything that was asked of her was mediated through Peter. Peter continuously drew her attention to Tiger and how to hold Tiger and what Tiger thought about rolling from side to side.

We were nervous when the technician asked if she could void her bladder since he wanted data and images once her bladder was empty. However, we had brought her portable potty along, and this, too, went smoothly. By the end of the second ultrasound session, Cecilia was still calm, happy to receive praise for doing such a good job, and occupied with how Tiger needed to take a bath because she had placed him on the hospital floor so he could go “potty” too.

This was, by far, the most painless ultrasound experience we have had to date.

urine sample

Cecilia has needed to give a urine sample at most of her doctor and hospital visits because of her underlying kidney disease. She has also has a history of repeat urinary tract infections, so urine samples have been required with each of these visits.

history

Getting urine samples from a baby or toddler can be a complete nightmare. For most of her life, we’ve used the bag method which is unreliable and impossible to keep sterile. Trying to obtain a bag sample would result in me bagging her, walking her, reading to her, and trying to distract her (sometimes for hours) while I waited for her to pee. When she did pee, it would sometimes entirely escape the bag, and I would have to start the whole process again. When I finally got the sample, the doctors would often say it was unusable due to contamination.

The worst times occurred when a constipated Cece released tiny bowel movements contaminating multiple urine bags in a row. Her skin would become raw and irritated from the bags being attached and removed one after another. These were the experiences that led to me asking if she could just be catheterized to obtain a clean sample. But catheterizing came with its own trauma, as she was forcibly held down, cleaned, and the catheter was attached. For multiple days after being catheterized, she would be sore and bruised and begin to cry every time she passed urine.

materials

- 1 stuffed animal

- 1 portable potty

- 2-3 sterile urine cups (you can ask the hospital for these for free)

method

Potty-training Cece has been a long and exhausting journey, which has included battling the demons of constipation and urinary tract infections, both of which properly deserve their own posts. But after months of exhausting routine, meltdowns, showers, and sterilizing of bathrooms, Cece is finally potty-trained.

Despite this, we knew she couldn’t possibly understand how to hold a sterile cup underneath her while she peed into it. But on long day trips away from home, Cece has asked to go potty, and we have brought her little portable potty with us so she doesn’t need to use a public bathroom. She has successfully peed into this potty multiple times, so we theorized that if we placed a sterile cup inside the potty, the cup might catch some of the urine.

why this works

Cece did not know the cup was inside of her potty, so going pee in her potty remained a totally familiar part of her routine.

results

When the ultrasound technician asked if Cece could void her bladder so that he could obtain images with her bladder empty, we were very nervous, since we hadn’t practiced it. Peter suggested to Cece that Tiger needed to go potty and asked if Cece would like to go potty too. Cece said, “Yes, please,” and with the technician’s permission, we placed the potty on the floor in the same room where the ultrasound was being done. Cece happily sat on her potty and peed a tiny amount, then stood up, saying, “I’m all done.”

The technician informed us of the millimeter content of urine present in her bladder and said she needed to empty it more fully. Peter said that Tiger was not yet finished going potty and asked if Cece could sit back on her potty. She agreed, placed Tiger on the floor next to her and told him to go potty.

I could feel the pressure and attention building on Cece and redirected it to myself by initiating conversation about how important the post-voiding images were. I told him frankly that if she couldn’t pass urine in this time frame, we were not going to worry about it for today. However, as I said this, we all heard a stream of urine being released and turned to see a huge smile on Cece’s face. Simply redirecting the focus to myself gave her the space to do what was being asked of her.

The urine cup was full and we capped it and dropped it off at the lab while it was still fresh on our way to our eye appointment.

This was, by far, the most painless urine sample experience we have had to date.

blood pressure

Cece needs her blood pressure checked at every nephrology appointment, urgent care visit or emergency room visit.

history

Cece has cried through every blood pressure check, not understanding why a stranger is touching her and squeezing her arm with a machine until it verges on pain. The fear and anxiety are typically crippling for her and she would frequently cry the minute the cuff started to constrict.

Eighteen months ago, her previous nephrologist suggested that Cece be put on blood pressure medication because her numbers were reading so high. I argued with this suggestion, countering that Cece had been crying/screaming throughout each of their readings and asked if I could have some time to calm her down before we try again.

After books and a snack, we tried again with only one nurse remaining silent in the background and my voice and hands guiding Cece through the process. She whined only slightly, but her numbers were well within the normal range. The nephrologist grudgingly agreed that blood pressure medication was unnecessary with such low numbers.

materials

- 1 stuffed animal

- 1 pediatric blood pressure cuff (you can ask the hospital for one of these for free, or you can just use your hand)

method

The morning after one of Cece’s emergency room visits, I walked into Cece’s room to greet her good morning, and she rolled over and told me, “The doctor squeezes my little arm.”

“I know, my darling,” I said. “The doctor was trying to take your blood pressure.”

She then wrapped one of her hands around her opposite arm and squeezed it as hard as she could, then pretended to cry.

In the weeks leading up to her visit, we used our hands to mimic the gradual pressure of a blood pressure cuff around her arm. Peter would frequently mimic noises of the blood pressure machine constricting and releasing since Cece is so sound-driven. Sometimes, we counted or asked her to point to her nose, eyes, mouth, or ears. We always praised her afterwards and told her how good of a job she did.

why this works

Making blood pressure checks part of her routine and involving counting or simple games helps redirect her focus from the discomfort. When one of her parents is performing the check instead of a strange nurse or doctor, she is much more able to accept and process what is happening.

results

By the time we entered the room for her nephrology appointment, Cecilia was thoroughly preoccupied with how she was asked to sit on the hospital bed and wanted to initiate and redo the sitting by herself. While Peter was walking with her through this, I redirected the nurse’s attention to me and made slight conversation regarding Cece’s need for time to initiate, understand, and process what was being asked of her.

I politely asked for patience and if we could give her a few minutes. The nurse was kind and agreed, and when Cece had completed her sitting down by herself, Peter asked the nurse if everything that was said to Cece could go through him.

The nurse was content to remain in the background and Peter suggested that Zebra take his blood pressure and used a silly voice for Zebra to agree and then squeezed and released Zebra. He then asked Cece if she was ready to take her blood pressure, and she said, “yes, please.” He asked Cece to squeeze his hand while her arm was being squeezed and she laughed as her arm was squeezed and released. Peter and I both praised her.

This was, by far, the most painless blood pressure check we have had to date.

vital signs

Cece’s vitals are taken at every pediatrician, doctor, or hospital visit but urgent care facilities, emergency rooms, and hospitals regularly attempt to push her too quickly through the process of taking her vitals.

history

Cece does not respond well to being run rapidly through a vitals check. Time after time, she has tried to listen, focus, and understand what is happening, then becomes quickly overwhelmed, begins to panic, and starts to cry and scream.

materials

We have these items on hand at home, but they are also readily available online.

methods

We use the same techniques as described above to practice taking Cece’s temperature and oxygen levels, look into her ears, listen to her heart and lungs, and check her height and weight. These techniques include:

- using stuffed animals to mimic the desired behavior

- using stories or games to distract during the pretend procedure

- having the procedure performed by a beloved parent

- practicing daily or every other day leading up to a doctor’s visit

why this works

Routine practice of these things allows Cece’s understanding of what they are to build slowly over time. She is given days instead of minutes or seconds to process what is happening to her, and she loves and trusts the people who are guiding her through it instead of submitting herself to a stranger that she cannot see who is often impatient with her, which only compounds her fear.

results

Before her nephrology appointment, Cece was run through a vitals check by an impatient male nurse. It was towards the end of our hospital visit, and everyone was exhausted. I could tell Peter was feeling pressured by the nurse and consequently pushing Cece through the process a little too fast. I told the nurse we needed a few minutes for her to process what was happening and respond accordingly. I also asked him to allow Peter to be the one to speak to Cece and to walk her through what was needed.

He agreed, and everyone calmed down noticeably. Peter was able to calmly participate in the call-and-response pattern that prevented Cece from spiraling into panic. Although we came close to a meltdown, we were able to neutralize the situation.

This vitals check was the most painless one we have had to date.

benefits of play therapy

Overall, this past hospital visit was unequivocally our most smooth and least traumatic visit to date. We attribute this in part to Cece’s age and increased capacity to understand what “doctor” and “hospital” mean, but we also attribute it to our use of play therapy.

benefits for Cecilia

From infancy, Cecilia has been been routinely traumatized by her visits to the doctor or hospital. Medical intervention in her early life caused Cecilia significant mental and emotional damage that we, as her parents, have to cope with every day of her life.

I am not attributing blame; I am merely stating reality.

For Cecilia, medical play therapy allowed her to process what has happened in the past and will happen in the future. Play therapy gives her the time, space, and experience to grow in understanding and acceptance at her pace.

Day by day, little by little, she began to remember all the steps involved in ultrasound practice until it became a routine and enjoyable bonding experience between her and her parents. By the time she experienced the real ultrasound, she had built up enough experience that fear and panic didn’t overwhelm and eclipse her.

Play therapy gives Cecilia a sense of agency in what happens to her mind and her body. Guided by parents who love her, she is able to respond, consent, and process experiences that were once nothing short of conscious nightmares for her. Play therapy anchors her in the familiar, the known, the encountered, and gives her a sense of confidence about what has happened and is going to happen.

The greatest benefit of play therapy for Cecilia was the gift of time that it gave her. She has never and likely will never be able to comprehend, react, or respond to circumstance and environment as quickly as someone who is sighted can.

Allowing her to encounter medical procedures in the safety of her own home, her own room, and her own bed (along with her parents guiding the process) stripped it of its inherent terror. She had days and weeks to absorb and piece together what happened before, during, and after this practice. Over time, she built up trust in us and confidence in herself that allowed her to conquer her anxiety and fear.

benefits for us (her parents)

Because science and medicine have become virtually deified in our culture, today’s parents often feel that they need to obey, submit, and surrender to medical authority. We feel socially pressured to offer gratitude and humility in the face of medical expertise. A lifetime of this can lead to feelings that we are not in control of our lives, our bodies, our children’s lives, or our children’s bodies. We can feel like choices are being made for us–like we are passive participants in what is happening to us or our children–like we are victims.

The primary benefit of medical play therapy for parents is that it restores a sense of agency to the parents. Medical play therapy is something that is within the realm of our choice and control; we are able to decide and enact something that directly helps our children process their lives and their bodies. Rather than feeling like we are standing by and watching our children suffer, we are able to feel like we are empowering our children to understand and process their fear, pain, and trauma.

As parents, Peter and I walked into this most recent hospital visit feeling more prepared and in control than we ever had before. Throughout the duration of that long and exhausting morning, we never felt like things were spiraling out of our control into terror, panic, and chaos. Instead, we systematically approached each upcoming obstacle with intention, patience, control, and confidence.

Medical play therapy prepared us to know how to speak to Cecilia and guide her through the moments where she was stuck, confused, or beginning to panic. It built confidence in ourselves and our relationship with Cecilia to carry all of us through what would inevitably be a tiring and trying day.

We walked away from the hospital feeling like we hadn’t betrayed or terrorized Cecilia. We walked away feeling proud of her and proud of ourselves. We walked away in control and in confidence.

We walked away as agents rather than victims.

why play therapy isn’t enough

As prepared as we felt and as beneficial as play therapy was before, during, and after our most recent hospital visit, there is simply no way to prepare for every potential interaction or circumstance.

This is where patient advocacy comes into play.

Advocating for your child during medical interventions is something that should be intuitive–but isn’t. As parents, we feel that we are protecting and serving our children’s best interests by submitting them to medical expertise, regardless of whether or not those interventions terrorize or traumatize the child in the process.

However, we do not know (and medical professionals do not know) that the choices that they are making for our children are ultimately and actually the best choices. We are all–always–making educated guesses and the history of medicine is littered with suffering and dying people who have paid for the mistakes of medical professionals.

patient advocacy

I truly believe that the majority of medical professionals enter their profession out of a genuine desire to help heal the sick, suffering, and dying. But the medical industry is massive and complex, and no one individual’s intentions are capable of remaining perfectly pure in the face of industry, insurance, lawsuits, overwork, and compensation.

There is simply no getting around the reality that no one professional individual, whether doctor or lawyer or therapist, is as invested in the mental and physical health of our children as we are. Similarly, the experts whose job it is to serve the best interests of our children regularly make choices that only those children and their parents have to live with.

At the end of every day, we, as parents, are our children’s best offense, defense, and path forward.

We are also the experts on our children. No professional offering a professional opinion has clocked the sheer number of hours observing and engaging with the individual case study that each child is. It is our job as parents to take each professional opinion and integrate its place within the complex jigsaw puzzle that is each individual child.

The heart of patient advocacy comes from this confidence in ourselves as parents to be more invested in our children’s health and more aware of the potential risks and benefits behind each decision that we make for our children. It consists in the self-awareness and strength to be able to challenge or resist protocol, procedure, or pressure when we know that it won’t serve the best interests of our family or our children.

Patient advocacy requires placing trust in ourselves and our children over and above trust in medical professionals. It requires us to walk that delicate line between utilizing medical expertise to serve our children’s best interests and preventing medical expertise from utilizing our children to build a data pool.

Medical play therapy can help to prepare both parents and children to walk through a doctor or hospital visit with confidence and trust. However, when circumstances inevitably arise that were not practiced, parents must adapt to the situation at hand accordingly.

Elements of play therapy can still be useful in these contexts; for example, when Cecilia needed to void her bladder in the middle of the ultrasound, and Peter told her that Tiger needed to go potty and asked if she wanted to go potty too. But even play therapy can only carry us so far when silent pressure is being placed on us or our children to perform within a specific time frame.

advocating for patience

Even the best-intentioned medical practitioners work most days in a world where they witness an endless stream of sick, suffering, and dying humans. It is impossible for them to not build up some psychological defenses against this over-saturation of pain.

Over time and without intention, they slowly become numb to the sound of children screaming and crying, of the sick and elderly moaning or begging, of parents pleading or arguing. It is work for them, and they are forced to compartmentalize it in order to do their jobs.

In some cases, this ubiquity of pain and trauma can lead to medical professionals being impatient or insensitive. It is the rare nurse or doctor who can retain profound patience and gentleness without communicating silent, passive pressure that the patient and his or her family need to get on with it.

As adults, we can comprehend that these individuals are just trying to do their jobs, and we can be cooperative in the process. But our children do not possess the neurological infrastructure necessary to grasp and compartmentalize this reality. Instead, our children become frozen in anxiety, then fear, then panic. They can even develop feelings of betrayal and grief if their parents do not mediate these interactions.

With a child like Cecilia, it is beyond necessary to remind nurses and doctors when they need to take a step back and give her some time to process what is being asked of her or what next needs to be done to her. As she grows older, I find myself reminding even beloved family members that they need to give Cecilia time to process before expecting her to respond or pressuring her for a response.

When encountering strangers that see Cecilia only as the next patient in line, it is critical to prevent them from forcing her through a routine procedure that she isn’t ready for or doesn’t understand.

Patience is not an American virtue. We don’t prioritize or promote patience in our culture. And yet, patience has the power to prevent us from saying or doing so many things that we may otherwise end up regretting. It has the power to make us more mindful of what we choose to say and do. It has the power to make us into better parents and our children into better adults. It has the power to prevent great harm.

big girls don’t cry

Three weeks ago, I asked Cecilia to lay back in her bed so we could practice her ultrasound. As she was laying down, Cecilia said, “She lays in the bed because the doctor is mad at her.”

Brushing her hair off her forehead, I leaned down to kiss her brow and responded, “The doctor isn’t mad at you, baby. The doctor is trying to help. The doctor is trying to take pictures of your little tummy.”

But Cecilia only replied, “I’m so sorry, Mom. I forgive you.”

Desperate to make her understand, I said, “You didn’t do anything wrong, baby. The doctor isn’t mad at you. You don’t need to apologize.”

Blinking slowly at me, Cecilia only repeated, “I forgive you. I forgive you. I forgive you.”

Holding back tears, I gave the response she was seeking and said, “Mommy forgives you, baby.”

Each time this type of interaction happens, I feel like I am failing Cecilia as her mother. She has no comprehension of what has happened or is happening. Apologizing and receiving forgiveness is merely a verbal formula that she needs to complete before she feels she move on to what is being asked of her.

A few months ago, I was washing her hair in the shower, and she said to me, “The doctor makes me feel sad, Mom.”

What can I say to this? How can I relay to Cecilia the history of her birth, her diagnosis, her prognosis? How do I possibly justify decisions I have made for her and continue to make for her? How can I sputter meaningless reassurances that the doctor isn’t mad at her, that she hasn’t done anything wrong, that she doesn’t need to apologize?

There are times to painful to recount, moments I cannot describe of watching Cecilia’s face crumple with pain, fear, and intense determination as she compulsively repeats, “She doesn’t need to cry; she doesn’t need to cry; she doesn’t need to cry!”

Having a child with a complex medical condition can make a parent feel like no matter what choice he or she makes, it will be the wrong one. This type of lived experience puts parents face to face with the mystery and terror of human existence. It makes us question the most fundamental things. It makes us fear that what we are and what we have to offer will never be close to enough.

Our daughter Cecilia is a superhero, but she doesn’t know it. Despite all of her past fear and trauma, she said to me and Peter the morning of her hospital visit, “Let’s go to the doctor! It will be so much fun!”

Peter kissed her on the forehead and told her that she was such a big girl and that big girls don’t cry. He told her that once we were done at the hospital, we would go to the grocery store and get her some chocolate.

She giggled maniacally and happily exclaimed, “Chock-it!”

In J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, chocolate is used to combat the terror and helplessness induced by dementors, which are undead, wraith-like creatures that leech the happiness from human beings and can suck out the souls from human mouths.

I sat quietly in the front seat of our minivan, trying to conceal my own nauseous anxiety, and thought that chocolate seemed like an apt antidote for a hospital visit.

Cecilia did not scream, cry, or meltdown once that day. The night before, we had prayed with her that Cecilia would have the strength to trust Mom and Dad to protect her. She went through an ultrasound, a urine sample, an ophthalmologist visit, a nephrologist visit, and optical photography–all with total confidence in us and in herself. For perhaps the first time in her short life, she felt secure at the hospital.

As we were pulling out of the parking garage, Peter played “Big Girls Don’t Cry,” by Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons. We stopped off at Mom’s Organic Market to pick up some fresh vegetables and dark chocolate. When asked what she wanted to eat, Cece answered, “Chicken and avocado!” so we drove to a Mexican restaurant and ordered chicken fajitas and a molcajete full of guacamole.

I sat next to Cece in our tight, brightly-colored booth and kissed the top of her head. Waving her hands in excitement, a smile breaking like a wave across her face, she exclaimed to me and Peter, “I went to the doctor! I did my ultrasound! I did a good job!”

My chest swelled, and my breath caught in my throat. How does one speak when words are clearly not enough? I turned my face into my elbow and took a minute to sob soundlessly. Then I pulled myself together, put my arm around my daughter, and said quietly, “Yes, baby. You did.”