Take Back Your Health (Part 1): The Burden of Disease

What is “health,” and what does it mean to “take it back”?

Everyone struggles with health issues, but today, many of us are finding ourselves with chronic disease as early as our teenage years. The world surrounding us is becoming increasingly toxic, and many things that are marketed to us–including those that claim to boost health–have hidden toxicities.

medical advice disclaimer: This website does not provide medical advice and is intended for informational purposes only. Any statements or claims about the possible health benefits conferred by any foods or supplements have not been evaluated by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and are not intended to diagnose, treat, prevent or cure any disease.

born into a toxic world

Health is a basic right of every human being. It is also the foundation that every person requires in order to accomplish pretty much anything. Despite propaganda that says the contrary, our government and medical institutions are riddled with conflicts of interest and ethical issues surrounding what is commercially available to the public and marketed as “healthy.” This is seen most dramatically in such cases as the emails exchanged between Coca Cola and the principal researchers in the International Study of Childhood Obesity, or the fact that Nestle’s intensive marketing of infant formula is now believed to be responsible for millions of infant deaths in low-and-middle-income countries.

The prospect for both life expectancy and quality of life for future generations does not look promising. As early as 2005, a special report in The New England Journal of Medicine warned:

Unless effective population-level interventions to reduce obesity are developed, the steady rise in life expectancy observed in the modern era may soon come to an end and the youth of today may, on average, live less healthy and possibly even shorter lives than their parents.

“A Potential Decline in Life Expectancy in the United States in the 21st Century”

As parents, it feels impossible to trust the health of our children or our families to anyone but ourselves. However, the sheer quantity of conflicting advice, opinions, and established “science” that is out there can be overwhelming, exhausting, and even stagnating. As a result, we often default to what the “experts” recommend.

In considering the health of ourselves and our children, sometimes we just don’t know where to begin. But often, the best place to begin is also the simplest.

in search of a definition

Health is a dynamic, multi-faceted, and complex concept. To cope with the complexity, we tend to separate health into “physical,” “mental,” or “social” categories.

The condition of being sound in body, mind, or spirit, especially : freedom from physical disease or pain; the general condition of the body.

Merriam-Webster

Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

World Health Organization

The WHO definition of health as complete wellbeing is no longer fit for purpose given the rise of chronic disease. . . [we] propose changing the emphasis towards the ability to adapt and self manage in the face of social, physical, and emotional challenges.

the bmj

A contemporary definition of health recognizes that disease and disability can and often do co-exist with wellness. In this new conception, health is transformed from a state that requires the absence of disease to a state where the central theme is the fullness of life.

Military Medicine

With the “rise of chronic disease,” we began to search for a new definition–one more complex than just “the absence of disease or infirmity.” Over the past century, more and more people have begun to suffer from diseases that are not immediately fatal, but which have serious implications for quality of life. These include disability, routine interventions/treatments, and dependence on prescription medication.

What was once the “absence” of disease has become finding a way to live with disease. How did this happen? Are our standards diminishing, or are we simply growing more realistic as we evolve? Is health something we should consider with entitlement?

When we think of human rights, we typically default to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Health is not listed among these things, but it is constitutionally protected. . . just not in the United States.

health as a human right

In 1946, the World Health Organization formulated a constitution, which outlines their basic principles and states unequivocally that health is a fundamental and basic right of every human person.

The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.

Constitution of the World Health Organization

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

Article 25, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, United Nations

The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. The steps to be taken . . . include those necessary for: The prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases; The creation of conditions which would assure to all medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness.

Article 12, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, United Nations

As seen in these three quotes, health is considered a basic human right by both the World Health Organization and the United Nations. In 1977, the United States signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (cited above). In 1943, President Roosevelt proposed a second “Bill of Rights” that included health as a human right, but it was never passed. Despite these legal precedents, the political battle disputing whether or not the right to health is a moral right or a legal right continues.

Among all the rights to which we are entitled, health care may be the most intersectional and crucial. The very frailty of our human lives demands that we protect this right as a public good . . .Without our health we—literally—do not live, let alone live with dignity. In the United States, we cannot enjoy the right to health care. Our country has a system designed to deny, not support, the right to health.

American Bar Association

The United States is notorious for advocating and protecting human rights; so why doesn’t it consider health as a human right? This question is far bigger than most of us will ever be able to answer. Instead, we accept the rather confusing combination of public and private healthcare that operates in the United States and merely attempt to protect our family’s health where and when we can. But for those of us who struggle financially, this can be challenging. Whether it’s health insurance, nutritional supplements, or a gym membership, being “healthy” costs money.

health as a commodity

The adage “health is wealth” is indisputable; without health (mental or physical), our human capacity to accomplish anything is vastly limited. However, in today’s world, health also requires wealth, as evidenced by the following statistics:

- According to the Global Wellness Institute, the global wellness economy was valued at $4.9 trillion in 2019 and is projected to reach nearly $7.0 trillion in 2025.

- The Global Wellness Institute ranks the United States as “by far the world’s top wellness economy,” valued at $1,215.7 billion.

- A 2021 article in Pharma-Nutrition reports that the global supplement and nutraceutical industry was worth almost $353 billion USD in 2019.

- Nerdwallet ranks personal trainers and personal wellness among the 23 most profitable businesses in 2023.

- WordPress lists health and fitness as the #1 most lucrative blogging category, beating out personal finance in 2nd place.

Health and wellness are no longer just necessary foundations to all forms of human endeavor; they have become businesses and industries in themselves. There exists a stark difference, however, between the glamorous marketing of the booming wellness industry and the ubiquity of chronic disease in the United States.

For every human person, health–or the lack of it–is an inescapable reality.

the reality of American health

Mortality statistics are hard for anyone to read, especially for those of us who have experienced loss from 1 of the 10 leading causes of death. Many of us have personally known or watched someone close to us succumb to heart disease or cancer. These 2 major killers dominate more than half of all deaths from the 10 leading causes. Every human death means a family grieving, and this aching reality is obscured when we’re looking at hundreds, thousands, or millions of people. Despite this, it is one of the most effective means we have to measure American health as it currently stands.

- Roughly 13 million Americans are diagnosed with heart disease, which is ranked as the #1 cause of death, with mortality reaching 695,547 in 2021.

- Cancer is ranked as the 2nd cause of death, with mortality at 605,213 in 2021.

- In 2020, obesity levels reached 41.9% for adults, 22.2% for adolescents, and 20.7% for children.

- In 2019, 38.2 million Americans had type 2 diabetes as their primary diagnosis.

- In 2018, 6 million adults had diagnoses of kidney disease, and 4.5 million had diagnoses of liver disease.

- In 2021, Alzheimer’s disease was ranked 7th in the top 10 causes of death, with mortality reaching 119,399.

- In 2021, infant mortality was 543.6 per 100,000 live births, for a total of 19,920 infant deaths.

- In 2021, maternal mortality was 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, for a total of 1,205 maternal deaths.

Some of these numbers are so large that they become virtually meaningless. The faces that belong to these people fade behind the sterile, bright white pages of the National Center for Health Statistics. And yet, death and disease are inescapable realities of human life, and everyone will die of something, someday.

So how do we gain a more accurate picture of what American health really looks like? By measuring it against the health of other high-income countries.

from a global perspective

According to the United Health Foundation, the United States ranked #29 out of 38 countries for life expectancy and #33 out of 38 for infant mortality in 2019.

According to the World Economic Forum, the United States spends more on healthcare than any other country, at $12,318/person in 2021 compared with Germany’s $7,383/person. This amounts to nearly twice as much as other high-income countries, such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan and Australia.

questions worth asking

- Why is the United States willing to sign an international covenant that guarantees health and healthcare as fundamental human rights, but is unwilling to implement similar protections at home?

- If the United States spends nearly twice as much on healthcare as other high-income countries and ranks as “by far” the top wellness economy in the world, why are its health statistics so abysmal?

- Given these statistics, is it realistic to define health as the “absence of disease and infirmity,” or do we need a new definition?

The WHO definition of health as complete wellbeing is no longer fit for purpose given the rise of chronic disease. . . [we] propose changing the emphasis towards the ability to adapt and self manage in the face of social, physical, and emotional challenges.

The bmj

the rise of chronic disease

A clean answer to the problem of American health might be that we are just living longer because we’ve largely eliminated fatalities from infectious disease, and, thus, the burden of death has shifted to diseases that simply kill more slowly.

In fact, a general consensus holds that infectious disease has been largely neutralized as a primary cause of mortality by advances in sanitation and medical technology. This opinion also admits that the increased lifespan and an aging population together have resulted in a higher prevalence of noncommunicable diseases.

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are not contagious/infectious; they cannot be transferred from one person to another. In other words, they arise internally, not externally. Examples of NCDs include heart disease, cancer, chronic lower respiratory disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Of the 10 leading causes of mortality in the United States, 8 are NCDs.

NCD statistics

- A person dies prematurely from an NCD every 2 seconds.

- 85% of premature deaths occur in low-and-middle-income countries.

- NCDs cause more than 3 out of 4 years lived with a disability.

- Mortality from NCDs has been rising steadily since the year 2000.

- In 2011, NCDs caused 63% of all deaths.

- Today, NCDs cause 74% of all deaths.

- 41 million people die globally from NCDs every year.

NCDs additionally place enormous burdens on economies and acutely increase an individual’s risk of susceptibility to infectious disease:

Evidence shows that NCDs and their risk factors increase the likelihood of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 across all age groups . . . NCDs can affect vulnerability to illness, pathogen performance, and the ability of health systems to handle health threats. High rates of NCDs perpetuate poverty, strain economic development, and burden fragile health systems, making countries less resilient. . .

“NCDs and Global Health Security,” Centers for Disease Control

causes of NCDs

The World Health Organization states that NCDs “share key modifiable behavioural risk factors“ that include:

- tobacco use

- unhealthy diet

- lack of physical activity

- harmful use of alcohol

- overweight/obesity

- hypertension

prevention of NCDs

According to the NCD Alliance, “an estimated 80% of NCDs are preventable.” Top methods include:

- eating a diet rich in nutrients and antioxidants

- increasing physical activity and exercise

- decreasing or eliminating tobacco and alcohol use

- reducing exposure to air pollution

questions worth asking

- Why is NCD mortality steadily rising (rather than decreasing) with all our advances in medical technology?

- Why do NCDs disproportionately impact the poor, especially in low-and-middle-income countries?

- If NCDs are so deeply linked with diet and lifestyle choices, is it simply the fault of NCD patients for not eating or living the right way?

the global burden of disease

Data shows that NCDs are the greatest risk to human health that exists globally. As a population, we are more likely to die from an NCD than from anything else. It is even emphasized that NCDs increase our likelihood of dying from an infectious disease, such as influenza, tuberculosis, or Covid-19.

For more than 30 years, more than 7,000 scientists in more than 156 countries and territories have conducted research entitled, “The Global Burden of Disease.” The latest results from their research state,

A global crisis of chronic diseases and failure of public health to stem the rise in highly preventable risk factors have left populations vulnerable to acute health emergencies such as COVID-19.

The Global Burden of Disease

If we break that sentence down into phrases, we get the following:

- “global crisis of chronic diseases”

- “failure of public health”

- “highly preventable risk factors”

- “have left populations vulnerable”

Given this statement, it’s hard to believe that NCDs are just more noticeable because of an increased lifespan and an aging population. It’s hard to believe that NCD rates are steadily climbing because people are just lazy or stupid or irresponsible.

Despite constant advances in technology, people are growing more and not less sick–so sick, in fact, that we are considering redefining the word “health” to encompass chronic disease, disability, and management. Given the sheer weight of this global burden of disease, who can we hold accountable for the way these NCDs now cause us to live, suffer, and die?

chronic disease accountability

Nobody wants to believe that other human beings consciously and freely profit from the suffering and deaths of ourselves and our children. It’s not a thought that fosters good will towards men. But human creatures have shown themselves to be capable of much greater savagery than the white-collar brutality of today, mediated as it is through technology, celebrities, and lawyers.

tobacco industry

According to the Federal Trade Commission, cigarette companies spent a mere $7.84 billion on advertising and promotion to make approximately $203.7 billion in 2020. Meanwhile, in the midst of a respiratory pandemic, the tobacco industry and their 236 registered lobbyists spent $28,156,312 attempting to weaken tobacco policies. In the landmark 2006 United States v. Philip Morris case, the tobacco industry was found guilty of violating the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act in their 50+ year-attempt to discredit the science and research that links cigarette smoking with disease.

alcohol industry

According to the Federal Trade Commission, the alcohol industry spent $3.45 billion in marketing expenditures to make nearly $60 billion in 2011. In 2020, during the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased by 2.9% (the largest annual increase in over 50 years), and the number of deaths involving alcohol also increased from 78,927 in 2019 to 99,017 in 2020. And yet, the alcohol industry is expected to self-regulate its marketing, despite decades of public health data supporting the relationship between decreased alcohol use and increased public health safety.

More than 140,000 deaths annually are alcohol-related, but the laws governing alcohol marketing and consumption remain unchanged due to rampant conflicts of interest. A 2019 study concluded that alcohol industry actors “have been active in developing partnerships with governments across the world,” while this 2022 study reiterates that “alcohol companies continue to occupy prominent roles in health governance.”

fast food industry

Fast food restaurants spend roughly $5 billion annually in total advertising to make $331.41 billion in 2022. Approximately $1.8 billion involves marketing directly to children and adolescents. Pre-pandemic, 36.6% of adults and 36.3% of children and adolescents consumed fast food on a daily basis, and during/post-pandemic, fast-food-consumption surged. Fast food restaurants spent $318 million in 2019 to advertise on Spanish-language TV, and Black children and adolescents viewed approximately 75% more fast-food TV ads than their White peers.

Food industries have pledged self-regulation to protect public health, but have failed to follow through with these pledges. Companies such as Nestle, Kraft, and Dannon have “significant penetration” in low-and-middle-income-countries, which have the highest rates of NCDs. Moreover, a 2022 study found that 95% of the committee members of the advisory board for the 2020-2025 U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans had conflicts of interest with the food industry, especially Kellogg, Kraft, Mead Johnson, General Mills, and Dannon.

sugar industry

The sugar industry is worth roughly $13.5 billion, and sugar-sweetened beverage companies spend approximately $1 billion in annual advertising, including ads targeted specifically to children and adolescents. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the United States owns the world’s largest vertically-integrated cane sugar milling and refining operation, U.S. Sugar. Americans consume, on average, 17 tsp sugar/day, which is more than 2-3 the amount recommended by the American Heart Association, and the pandemic increased American consumption of sugar, particularly children’s consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages.

Sugar interests continue to obscure the science on the health effects of added sugar through a variety of tactics. They have attempted to discredit or downplay scientific evidence and have intentionally spread misinformation. They have hired their own scientists and have paid seemingly independent scientists to speak on behalf of the industry and its products. They have launched sophisticated PR campaigns to influence public opinion, and they have worked to influence the academic community including at scientific meetings and through the scientific literature.

Added Sugar, Subtracted Science: How Industry Obscures Science and Undermines Public Health Policy on Sugar

A 2015 investigation by the BMJ uncovered evidence of “the extraordinary extent to which key public health experts are involved with the sugar industry.” In particular, Coca Cola has a long history of using tactics similar to those of the tobacco industry. Emails exchanged between Coca Cola and the principal investigators of the International Study of Childhood Obesity reveal details disclosed surrounding the study design, presentation of results and acknowledgement of funding.

A 2013 study states that financial conflicts of interest were found in 6 of 17 studies on the relationship between obesity, cancer, diabetes, heart disease and sugar-sweetened beverages; each of the 6 studies with conflicts of interest concluded that evidence was “insufficient” to confirm or deny the association between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and NCDs.

budgets in perspective

Let’s do some simple math. How much do each of the major industries spend in annual advertising?

- tobacco: $7.84 billion

- alcohol: $3.45 billion

- fast food: $5 billion

- sugary beverages: $1 billion

How much is the Center for Disease’s Control annual budget for preventing and managing all diseases?

Roughly 1.4 billion.

In other words, the total amount spent on advertising by the 4 major industries fueling the chronic disease epidemic are more than 12 times higher than the CDC’s entire budget for preventing and managing disease.

questions worth asking

- Why do so many public health officials have financial relationships (conflicts of interest) with the tobacco, alcohol, fast food, and sugar industries?

- Why did the tobacco, alcohol, fast food, and sugar industries profit so much from the Covid-19 pandemic?

- Why doesn’t the CDC have a higher budget if they are expected to combat the ubiquity of tobacco, alcohol, fast food, and sugar consumption?

taking back our health

Most of the American public is utterly lost in the miasma of controversy surrounding what is “healthy” and what isn’t. Fad diets come and go, new studies “reveal hidden health benefits,” and different political majorities advocate different approaches to American health and happiness. If we, as parents, are struggling this much to figure out what is and isn’t true, our children don’t stand a chance.

It is neither just nor adequate to blame NCD patients for lack of self-discipline or awareness. And, although it feels just to blame the greed of the tobacco, alcohol, fast food and sugar industries, ultimately, this is not adequate either. Rather, a significant portion of accountability must be given to the public health officials (faceless and nameless as they are) who knowingly promote disease-causing products for financial or political gain.

Despite propaganda that says the contrary, our government and medical institutions are riddled with conflicts of interest and ethical issues surrounding what is commercially available to the public and marketed as “healthy.” As a result, our health and the health of our children is being taken from us by corporate and commercial interests that prioritize income more than human life.

Unless effective population-level interventions to reduce obesity are developed, the steady rise in life expectancy observed in the modern era may soon come to an end and the youth of today may, on average, live less healthy and possibly even shorter lives than their parents.

New England Journal of Medicine

As parents, we’re willing to do whatever it takes to give our children the happiest and healthiest lives we possibly can. And yet, we’re being told that our children are likely doomed to have a lower quality of life/life expectancy than we are. How do we respond to this? Nod and smile and make the best of it? Kneel down, bow our heads, and simply accept it for what it is?

For me, this is the point at which I decide to stand up and refuse to submit. Whether it’s pride, bravado, or a foolish inability to accept reality, I have decided to take back the health of my family and my children into my own hands.

But how exactly does one “take back” something as complex as health? Where do we begin, and who can we trust? Read the next post in this series, Take Back Your Health (Part 2): From Victim to Agent, to find out 🙂

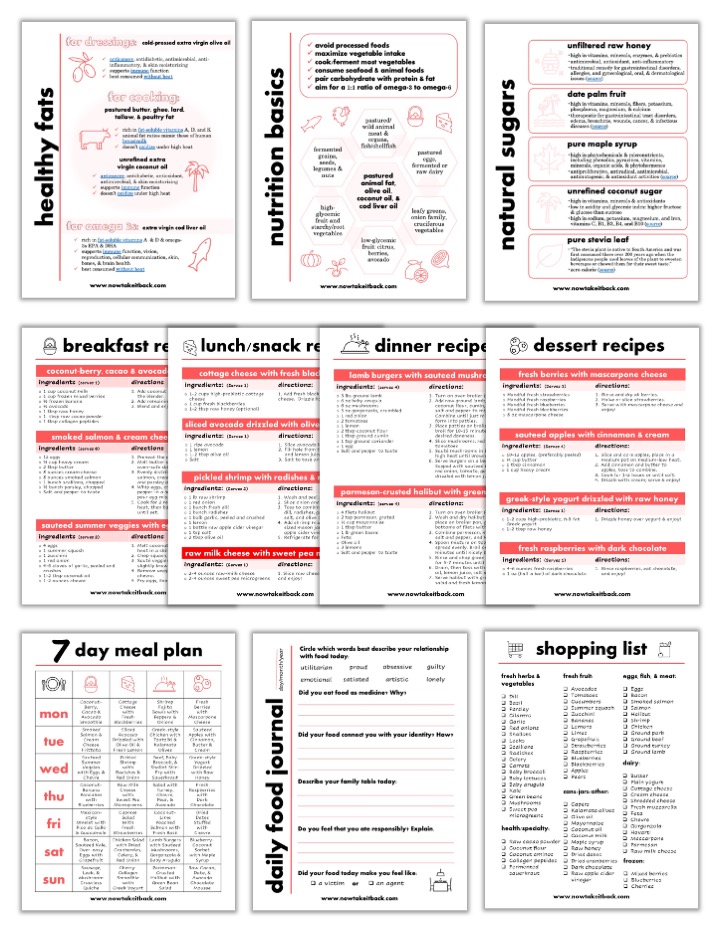

take my free 5-day challenge

& instantly access: