Take Back Your Health (Part 3): Food as Medicine

In Part 1 of this series, we explored what health is and which factors are driving the global burden of disease. In Part 2, we discussed why agency matters, where to begin, who to trust, and how to transform yourself from victim into agent. For most of us, this transformation begins with small, concrete steps that build on themselves over time. In order to move forward, we need to commit to change, and the best place to begin is diet.

Very few of us like to hear that “diet and lifestyle changes” can improve our health. That phrase implies a lot of troubleshooting, trial and error, and time on our part. On top of that, there doesn’t seem to be much of a consensus on how we should eat, and everyone seems to hold a different dietary theory. Nutrition can be boring, or nutrition can seem like a rabbit warren of conflicting opinion and advice. For most of us, filling a prescription or taking a daily multivitamin is just a lot easier.

So why all the emphasis on food and nutrition? Is the science really that clear? Is nutrition really the foundation of good health?

medical advice disclaimer: This website does not provide medical advice and is intended for informational purposes only. Any statements or claims about the possible health benefits conferred by any foods or supplements have not been evaluated by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and are not intended to diagnose, treat, prevent or cure any disease.

why nutrition?

The Centers for Disease Control states that nutrition plays a direct role in longevity, as well as disease prevention and management. According to the Center for Science in the Public Interest, approximately 678,000 deaths each year in the U.S. are directly attributable to inadequate nutrition.

malnutrition

A 2013 Global Burden of Disease study carried out in 188 countries found that dietary risks accounted for 11.3 million deaths and 241.4 million disability-adjusted-life-years. Moreover, malnutrition is deeply interlinked with the occurrence, development, and prognosis of all noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), especially colorectal cancer, the 3rd most common cancer in the world. Diet can both take and save lives; a high-trans-fat diet is a leading cause of ischemic heart disease, and a low-glycemic diet has the power to eliminate type 2 diabetes.

The World Cancer Research Fund identifies dietary patterns, antioxidant intake, body composition, prenatal diet, and breastfeeding as critical components in the development or prevention of cancer. The NCD Alliance lists malnutrition as a “major driver” of NCDs, with economically depressed populations and children being at greatest risk for overconsumption of sugary beverages, trans-fats, and ultra-processed carbohydrates.

hungry children

3.1 million children die from malnutrition every year; a child dies from hunger every 10 seconds. Globally, 974,956 cases of childhood obesity and 59,379 childhood deaths from diarrhea and pneumonia every year are attributable to lack of breastfeeding. According to the CDC, low rates of breastfeeding cost the United States more than 3 billion annually in medical bills for women and children.

Childhood obesity now affects 1 in 5 children in the United States. Over 1/3 of America’s youth (under age 20) have diagnoses of diabetes, and close to 1/3 of America’s youth eat fast food on a daily basis. Studies are now linking maternal hyperglycemia (high sugar intake) with increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and autism spectrum disorder in offspring.

the power of food

How is it possible that food can have such a substantial impact on our health? To put it simply, we eat multiple times a day, every day. In terms of both cumulative and compounding effect, food is intensely powerful. It could even be argued that with the exceptions of air and water, food is the most powerful driver of human life.

food as medicine

NCDs account for 74% of all deaths worldwide. What this means is that we are more likely to die from a NCD than anything else. And that’s just a mortality statistic. It is much harder to measure the impact that chronic disease will have on our energy levels, our will to live, our tolerance for pain and suffering, or our capacity to cope with a disability. According to the NCD Alliance, one of the most effective ways to protect ourselves from developing an NCD is high-quality nutrition.

Let food be thy medicine.

Hippocrates

Hippocrates (5th century BCE) is the original source of the Hippocratic oath, the oath upon which our modern medical oaths are based today. In ancient Greece, Hippocrates emphasized the role of diet and nutrition in disease prevention, but, today, modern physicians remain largely untrained in nutrition interventions.

Instead, institutions like the American Society for Nutrition have begun to initiate community-wide programs called “Food as Medicine” (FAM) to improve health literacy, mindfulness, and cooking skills. Similarly, the Rockefeller Foundation advocates “Food is Medicine” initiatives such as “produce prescriptions” and “medically-tailored meals and groceries,” and the National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute advocate a method of eating called DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) with successful community-wide meal programs.

Belief in food as medicine is growing, even on a political level. Further advances are being made by the Food as Medicine Coalition, which identifies itself as “an association of nonprofit medically tailored food and nutrition service providers” who work to promote public policy that supports a nutrition-as-medicine approach to chronic disease.

It is indisputable that food has a huge impact on mental and physical health. With the convergence of public and private initiatives promoting the centrality of food and diet for improving health, the time is ripe for clinical testing of specific approaches for the prevention or treatment of disease using food as medicine. Prescription pharmaceuticals are commonplace and widely accepted by patients, physicians and insurers. A dietary prescription should also be on the table.

“Food as medicine: translating the evidence,” Nature

Food is both medicine and fuel for our bodies on a biological level. But food also impacts us psychologically, socially, and culturally. Like health, nutrition is complex and difficult to define. Food has many dimensions, and each one plays a critical role in our health.

food as identity

Food is inseparable from culture. French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss argued that food culture is an alphabet, a shared language that reveals a society’s structure. Historically, food has been used both medicinally and religiously to navigate major life stages such as birth, marriage/pregnancy, and death. Food, both symbolically and ritualistically, has been interwoven with the religious and cultural beliefs of humanity for as long as we’ve had written history.

olive oil: Greece

Termed “the great healer” by Hippocrates and “liquid gold” by Homer, olive oil has been used in Greece for thousands of years, “not just for consumption and cooking, but also as perfume, anointment for the dead, soap, and lights,” as well as athletic and political rituals.

coconuts: Polynesia

Called “the Tree of Life,” the coconut tree provided musical instruments, eating utensils, cups, thatch, baskets, fans, brooms, torches, nets, lashings, rigging, games, food, hydration, and medicine for Polynesians, as well as playing an instrumental role in religious rituals and ceremonies.

cod liver oil: Norway

Called lysi (“light”) in old Norse, cod liver oil was an essential part of Norway’s economy, used for lamp fuel, tanning, paint, and soap, as well as forming an integral part of their diet and disease prevention; it was said that those who regularly consumed cod liver oil never fell ill.

cheese: France

For the French, cheese or le fromage, is interwoven with national identity, xenophobia, and agricultural history; always served at room temperature, it “may be sold bottled in oils, rolled in ashes, covered with mold, filled with seasonings, surrounded by rinds or waxes, or even in various stages of decay.”

blood & milk: east Africa

The Maasai tribe are modern-day pastoralists who still subsist off a traditional diet of blood and milk from their sacred cattle herds, which are deeply interwoven with their religion and economy and provide food, clothing, shelter, shoes, cooking and drinking vessels, currency, and salt.

fish & shellfish: Japan

Traditional Japanese food culture places an emphasis on fresh, raw, and seasonal seafood, from the first tuna catch of the season to the symbolic meanings behind lobsters and crabs (“celebration”) and sea bream (“congratulations”), as well as the food lore behind unagi (broiled eel) as protection against the coming heat.

rice: central India

Known as the “Rice Bowl,” the Indian state of Chhattisgarh has 70% of its population engaged in the agriculture of rice paddies, which is also the main staple of the local vegetarian diet and plays a central role in traditional economic, family, and social relations, as well as festivals and sacred rituals.

maize, beans, & squash: indigenous Americas

Termed the “Three Sisters” by indigenous peoples, intercropping of maize, beans, and squash was reflected in tales, myths, ceremonies, and legends about the “Three Sisters” sprouting from the body of Sky Woman’s daughter, a gift to the people as the physical and spiritual sustainers of life.

Food culture is integral to national and personal identity. Most of us grow up with familial food traditions in addition to our broader national food heritage. Food shapes our identity, but our identities are further shaped by our local and national communities. According to food archaeologist, Bill Schindler, sharing food is one of the elements that first made us uniquely human.

food as community

For most of us, food is a communal experience with profound social and cultural dimensions. When we consume food in isolation from one another, whether it be a microwaved television dinner or a utilitarian fast-food binge in the car, we lose the interpersonal, familial, and social dimensions of food.

the family table

So many of us view the kitchen as the heart of the home, but the family table also holds immense symbolism for belonging, place, community, family, conviviality, relationship, hierarchy, and home.

This past century has seen a shift away from the family table to eating on the couch or bed, usually in front of the television. Studies have shown that eating in front of the television results in a tendency towards overconsumption. More heartbreakingly, widows and widowers in older age are more at risk for nutritional deficiency because they lack a companion with whom to share the work and pleasure of food preparation and consumption.

At the family table, each person has a place or a designated chair. Children learn hierarchy (parents at the head of the table), social eating norms (manners, verbal engagement), and adult patterns of conversation. The table represents a time and a place to daily enter into ritualistic engagement with one another, marked by conversation and communal consumption of food. Guests are welcomed to the family table and served first as an indication of honor and hospitality.

In 2021, the American College of Pediatricians published a study entitled “The Benefits of The Family Table,” which include:

- higher grades in school

- higher intake of fruits and vegetables

- better familial relationships with parents and siblings

- improved language development (explanation, narrative, vocabulary)

- improved social skills and body image

- improved mental health

- decreased risk of depression and suicide

- decreased risk of obesity and eating disorders

- decreased risk of alcohol, nicotine, and drug use

- decreased risk of stealing, physical violence, or criminal behavior

- decreased risk of sexual activity

- decreased screen time

Getting back to the family table can help us reconnect with both our food and one another. When we don’t depend on television to mediate our interaction with our food or each other, we learn to re-encounter who we are to each other and ourselves in our particular environment. Taking back our family table can be an invaluable aid in taking back our health because it reminds us that food consumption is about more than nutrition; it is also about relationships.

“primary” food

Consuming food in isolation from other people can strip food of its social, emotional, psychological, cultural, and traditional elements. Just as health involves social, emotional, mental, and communal dimensions, nutrition involves more than just eating nourishing food high in macro-and-micro-nutrient content.

When I was studying to become a health coach with the Institute for Integrative Nutrition, great emphasis was placed on the idea of “primary food,” or the non-nutritive components of life that directly impact our health. These include healthy relationships, regular physical activity, a fulfilling career and a spiritual practice.

An abusive relationship or a toxic work environment can do just as much damage to our health as steady intake of fast food, alcohol, and nicotine. Relationships, whether personal, business, or spiritual, play a critical role in our health. We are communal creatures, after all. And one of the essential ways we commune with one another is through what we do or do not eat together.

food insecurity

Historically, one of humanity’s most challenging ethical problems is unequal access to nourishing food. Even our modern technologies have not resolved this fundamental human rights issue. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, roughly 2 billion people did not have access to enough safe and nutritious food in 2019. Moreover, food insecurity is directly linked with diet quality; that is, even when people have access to “enough” food, the quality of the food is inadequate to meet basic nutritional needs.

[P]eople experiencing moderate food insecurity face uncertainties about their ability to obtain food and have been forced to compromise on the nutritional quality and/or quantity of the food they consume. This points to cost and affordability of nutritious foods as a key factor affecting food security and, consequently, diet quality.

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World

Fast food and sugar industries spend billions in promoting their products, making ultra-processed, shelf-stable, and nutrient-depleted “food” ubiquitous, cheap, attractive, and filling (see Part 1 of this series). This empty and dead “food” is heavily marketed to children and impoverished communities, creating a vicious cycle between poverty and NCDs, especially in low-and-middle-income countries.

High-income countries, such as the United States, are not faring much better. The Association of American Medical Colleges states that 54 million Americans face food insecurity, and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported to Congress that 23.5 million Americans live in food deserts. A 2017 report by the USDA found that the higher the food insecurity, the more the individual is likely to have 1 of the 10 most prevalent NCDs.

Moreover, hunger, food insecurity, and NCDs disproportionately impact racial and ethnic communities. A 2019 study found that from 2001-2016, food insecurity rates for non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaskan Native households were at least 2x higher than White households. In 2021, 20% of Black people lived in food insecure households, and Black individuals are 3x more likely to experience hunger than White individuals.

NCDs, nutrition, and disease prevention are inextricably linked with food ethics, broken food systems, and food insecurity. They are massive topics in themselves and can be emotionally draining and overwhelming to contemplate. It is important, however, to emphasize the scope of the problem if we are trying to understand why nutrition matters. Our agency regarding what we eat, how we eat, and our access to nutritious food are privileges that nearly half of the modern world simply doesn’t have.

food as responsibility

Almost 3.1 billion people could not afford a healthy diet in 2020. Those of us who have the time, energy, and internet access to do our own research are among the world’s privileged few that have the resources and agency to change the way we eat and how we live. If we acknowledge this privilege, it’s only a short step further to acknowledge the responsibility that comes with it.

Education, resources, privilege, agency, and responsibility: these are the things that circumscribe the limits of our choices as parents and shape the world we give to our children. One of the greatest gifts we can offer our kids is a healthy body from infancy. And yet, more and more infants today are being born into bodies that are predisposed to disease from conception.

Why do close to 1/3 of America’s youth eat fast food on a daily basis? Because we have outsourced our food processing to companies who are interested in maximizing profit at the cost of nutrition. We have placed the responsibility of feeding ourselves and our children into the hands of strangers, restaurants, and faceless companies, and become willfully ignorant to what happens behind their closed doors.

What you eat impacts your health. What you buy impacts your culture.

Eating is a responsibility we have to ourselves, our children, our communities, our nation, and our world at large. How we eat and how we think and talk about food impacts those around us. As consumers, we have significant power to influence what is commercially available for consumption. When we give our food budget to the fast food and sugar industries, we increase their scope of influence. Alternately, when we give our food budget to local farmers, restaurants, or grocery stores that practice ethical food principles, we increase their scope of influence.

food as agency

When I was pregnant with my first daughter, I asked my midwives to tell me the most important thing I could do to optimize my pregnancy, labor, and delivery. Without exception, each one of them answered, “Diet.” Addicted as I was to Costco’s giant cinnamon muffins, it was not an answer I wanted to hear. It was, however, the truth.

Diet, food, and nutrition are immensely powerful; through them, we can optimize our fertility, pregnancies, and births or heal our bodies and minds. Through them, we can explore and express our identities and connect with our landscape and culture. Through them, we can interact with our community, both immediate and global. But perhaps most important of all, food and nutrition can be ways through which we activate our agency.

As described in Part 2 of this series, agency is our ability to freely make choices, and through those choices, impact our environment. From a global perspective, the scope of the problem when it comes to health and nutrition is enormous–much bigger than any one individual has the ability to solve.

Set your house in perfect order before you criticize the world.

Jordan peterson

As parents, a far more realistic goal is to improve our personal health and the health of our families–especially our children–through what we eat every day. Our diet is directly within the scope of both our responsibility and our agency; with nutrition, disease prevention can very literally be in our hands. Despite this, it can be overwhelming to learn something new, and this tends to be more true the older we become. This is why it’s best to begin low and slow.

case study: breastfeeding and the nature of human growth

Like many things in life, nutrition is compounding, meaning that it builds on itself. Many small changes combine to create larger change, but trying to change too many things at once can set us up for failure. It’s better to approach change slowly, in small amounts, and we can look to breastfeeding infants to teach us this lesson.

The human brain grows more quickly during the first 1,000 days of life than any other time. Breastmilk is nature’s “superfood” giving infants the micronutrients, proteins, growth factors, and hormones necessary for optimal brain growth. Breastfeeding additionally provides sensory, cognitive, social, and emotional education for the infant, all critical components to healthy brain development.

Breastfeeding infants consume small amounts of milk slowly to fuel this intense brain growth. The relatively lower protein content in the milk is similar to that of other mammals that keep their infants with them as opposed to higher protein content for mammals that need to leave their young to find food. When not kept to a feeding schedule, human infants naturally suckle frequently, drinking smaller amounts of milk often. Human nipples release smaller amounts of milk more slowly than artificial bottle nipples, and the work of nursing develops critical muscles in the mouth, jaw, and tongue of the infant.

We all began as infants, and we all experienced that first 1,000 days when our brains grew faster than any other time in our lives. As adults, we can learn a lot about learning from the behavior of breastfed babies. Here’s just a few lessons:

lasting change comes slowly, over time

try to learn only one new thing at a time

make time for rest and integration

practice a new skill until you gain confidence

you only fail when you stop trying

We’re all looking for quick wins, but the truth is that everything in life takes hard work, and if it doesn’t, it’s usually because someone else has done the hard work for us. Those things that we accomplish ourselves are usually the most lasting and the most rewarding. No one can activate our agency for us; only we can empower ourselves. And when we take it slowly, a little at time, we just may find that empowerment can begin as simply as walking into our kitchens and preparing our meals from real ingredients.

how to activate the power of food

For so many of us, food is directly linked with culture, tradition, memory, and emotion. And yet, food and how we approach its production and consumption also profoundly impacts our quality of life and longevity. Food is the method by which we take in the components that build our bones, blood, marrow, organs, and brains. In a very real way, it influences how we see the world, and in some cases, if we see at all.

Every bite of food you eat shapes the landscape your children will inherit.

joel salatin

When we begin to see food as a path to better health, we begin to notice all the daily ways in which small changes have compounding effects. Sourcing and preparing our own food is empowering, but it can also be simple–if we keep to 5 simple principles.

1. source real ingredients

Purchase only fruits, vegetables, eggs, meat, or fish that are whole and unprocessed. When we start with whole, real ingredients (whole avocadoes, whole crowns of broccoli, whole berries, whole eggs, etc.), we are forced to participate directly in the processing of those items. Purchase only minimally processed items such as high-quality fats (extra virgin coconut or olive oils) and cuts of meat or filets of fish.

2. process your own food

As a general rule, the more processing that occurs outside our kitchens, the lower the nutrition. Outsourcing processing means ingredients/foods that are more likely to be chemically altered, laboratory-produced, or exposed to light, heat, or oxygen (oxidized). If a food requires a lot of processing to make (say, a birthday cake), then we are not likely to consume that food except on special occasions when we’re willing to do the processing ourselves.

3. connect with your sources

Farmer’s markets and on-site farm stores are excellent places to begin reconnecting with our food. Even better is starting a garden, on any scale, in any environment, urban or country. Putting our hands in the soil and watching the sunlight, water, time, and life-energy that goes into growing a tomato or zucchini can do wonderful things for both our brains and bodies.

4. learn basic cooking skills

Cooking can be therapeutic and empowering. Even those of us who don’t like cooking can eat a real-food diet based on simple and quick recipes composed of high-quality ingredients. Teaching our children how to cook is another profound gift that will benefit them for life, and children are often delighted to participate in the more laborious aspects of food processing (peeling, chopping, stirring, etc.)

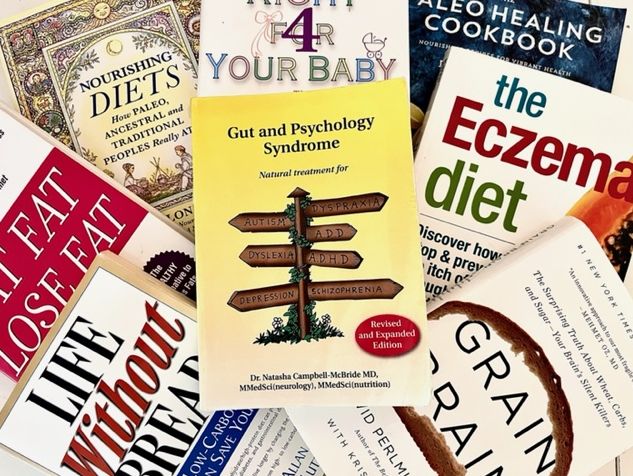

5. avoid diet ideology

Nutrition is not religion or politics, but diet ideology can make it feel that way. The reality is that there is no one-size-fits-all diet. Nutritional needs diverge by culture, community, genetics, geographic region, environment, and, most of all–medical history. It can be very tempting to be part of a community where everyone is eating the same way, but it can also be limiting. We can benefit far more by doing our own research, troubleshooting, and sticking to one basic rule: eat real, unprocessed food.

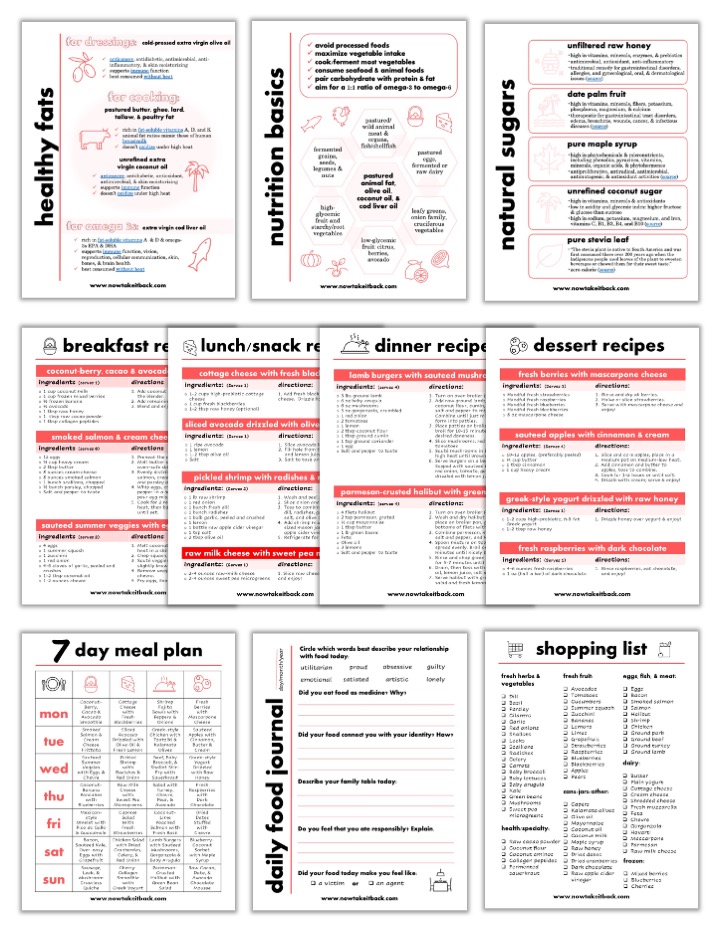

But what exactly does eating real, unprocessed food look like? What should we buy? What should we cook? Where do we begin? To answer these questions, we first need to tackle a much bigger question in the fourth part of this series: Take Back Your Health Part 4: Fat versus Sugar.

take my free 5-day challenge

& instantly access: